Introduction

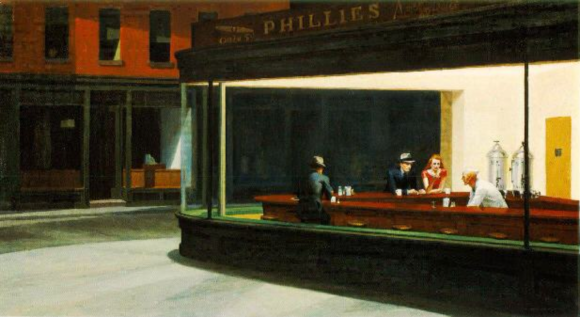

The popularity of the American realist painter, Edward Hopper (1882-1967) has continued to grow. His 1942 canvas, Nighthawks, has become an icon, especially for New York City, where he often found inspiration and painted. With popularity, however, comes an illicit traffic in many works that Hopper kept in storage and never intended for the market. This traffic includes many boyhood works and preparatory sketches from his mature years, as well as oil paintings from his formative years and his maturity. The illicit sales have been facilitated by dealers and auction houses, who have chosen to ignore provenance, the history or trail from the artist’s studio coming forth through successive owners. The suppressed story of how so many of Hopper’s works that he never intended to be on the market escaped from his estate needs to see the light of day. That such illicit sales stem from theft is a story waiting to be told: what flags attention is traffic in boyhood works, which Hopper neither gifted nor sold, first marketed right after his death. Hopper was notoriously reluctant to show his drawings from any period, which he did only rarely. So, it is no wonder that it was only just after his death that the market was suddenly deluged by his boyhood and preparatory sketches. How did such art that he never intended to be sold suddenly come to light? The question posed is where these works were stored and who found them and secretly began to put them up for sale.

This traffic in Edward Hopper’s art is illicit because all of these works, which were never sold or exhibited during his lifetime, formed part of his artist estate. He bequeathed his entire estate to his widow, the artist Josephine Nivison Hopper (1883-1968), who survived him only by months. With the exception of three of Jo Hopper’s own paintings and a piece of folk art, her last will respected Edward’s wishes and left all of his art, and all other art works that they owned including her work, to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Yet even before his widow’s will reached formal probate, when she died in 1968, just months after Edward’s death in 1967, some of his closeted boyhood works started to turn up at auction houses and galleries– anonymously– to conceal the consigner’s name. Still, the inexplicable appearance of these early works by Hopper did not provoke jealous attention by their rightful owner.

The Whitney Museum took no notice of these illicit sales, even though part of its rightful inheritance had been purloined and put on the market. These strange sales did not stir the museum. In fact, the museum itself had begun to sell some works by Edward Hopper from his widow’s bequest, including insider deals to collectors on its own committees. The museum’s sales from the Hopper bequest provoked from the New York Times a stringent protest by art critic Hilton Kramer, who claimed that the museum was destroying a legacy and wasting a cultural treasure. As if to save face and demonstrate cultural discipline, albeit tardy, the museum turned to the idea of producing a catalogue raisonné, a comprehensive catalogue of Edward Hopper’s work. For this project, the Whitney obtained from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation a grant with which in 1976, it hired me. I was then a young scholar in her twenties, who had just received a Ph.D. in art history from Rutgers University. My dissertation research had just won me the opportunity to serve as guest curator for an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The show, “Morgan Russell: Synchromist Studies, 1910-1922” received a favorable review from Hilton Kramer, which caught the Whitney’s attention. I could have no idea how this new mission at the Whitney would complicate my life.

My appointment at the Whitney drew praise from Hilton Kramer, in the New York Times, who saw it as a response to his earlier criticism of the museum. At the moment I was hired, the Whitney’s director, Tom Armstrong, warned me, “That’s the last good review you’ll ever get from Hilton Kramer.” But Kramer’s article reached a big readership: auction houses and dealers suddenly needed to confirm with me that works on the market were authentic and as such would eventually be included in the projected catalogue raisonné. The news that works on the market claiming to be by Hopper would require my approval alerted the man who had helped himself to works from the Hopper estate before it reached the Whitney. He, too, needed my authentication.

My need to document provenance was put to the test in my first month on the job. No sooner had the New York Times reported the project than a stranger paid a visit to my office, bringing with him a suitcase stuffed with works that he claimed were by Edward Hopper. The mystery only deepened when he identified himself as “Reverend Arthayer R. Sanborn,” a retired Baptist preacher from Nyack, New York, Hopper’s hometown. He was an unrelated neighbor to Edward’s boyhood home, who happened to live up the street in the house owned by the Baptist Church that he served. Sanborn expected me to authenticate these works, which later turned out were just a sampling of what he possessed, but he had no documentation or explanation of how they got into his hands from the artist. In short, he presented no proof of provenance or what is called “clear title.”

Lacking experience with either clergy or thieves, I got no help from the museum. At the Whitney, I took seriously my task and applied professional standards to the Hopper legacy. To create the required catalogue, I had to determine which works Edward Hopper had actually produced. Only art that my research authenticated would get into the catalogue. Not only did I need to retrace the trail of each object in public museums or still in private hands from the time that it had left the artist’s possession, but I also needed to study the artist’s papers. With the exception of four record books that Hopper and his wife kept whenever an art work left his studio for exhibition, sale, or gift, all other personal or professional documents kept by Edward or Jo were missing! There were no letters received, no notebooks or scrapbooks, no clipped reviews, no exhibition catalogues or books or magazines saved by the artist couple. I inquired about this strange absence of documentary material, when the estate had been bequeathed by his widow to the Whitney, but it went unexplained, even unquestioned by the museum.

In the course of research, however, I began to find clues as if pieces to complete a puzzle not yet clearly seen. I began finding other early works that had recently been sold at auction or by galleries that lacked provenance– because the consigner insisted upon remaining anonymous. Only much later, would I be able to put together all of these clues and figure out that the trail of the anonymous consigners led to Arthayer R. Sanborn, the local Baptist preacher; often I have been able confirm and document this conclusion beyond any doubt. How, I asked, did Sanborn get hold of so many works that the artist had kept in storage but should have passed to the Whitney, as specified by Jo Hopper’s last will? Sanborn’s claim that his cache had been gifted rang hollow in the face of contrary evidence. His and his wife’s stories of how that got these art works changed over the years in the course of several meetings that I held with them.

The Hoppers had carefully recorded every single gift of art in their extant record books and had never given multiple works to any individual. I was amazed to learn that Sanborn also possessed valuable documents, including the letters that Hopper had written to his family from his stay in Paris just after finishing art school. My wonder turned to dismay when I realized that Sanborn had amassed dozens of works in the published catalogue raisonné and hundreds of other drawings (that volume remains unpublished). When I first tried to bring this discovery to the museum’s administration, they dismissed it and urged me to hurry up and finish the catalogue. I wonder now and will probably never know if money changed hands: if the museum’s administration was paid off to do nothing about the huge theft, keep quiet, and figure out how to quiet me at the moment that I left the museum in June 1984.

I had put this history on the back burner until I read the Whitney Museum’s press release of late July 2017, announcing a gift of more than 4,000 documents from the papers of the artists, Edward and Jo Hopper. That the huge gift was mostly ignored by the press can be attributed to the Whitney’s strategy of releasing it just as the art world went on August vacation. However, I was shocked to discover that so many papers by Hopper and his wife existed and had been withheld for so long, not only from me, but from the public. The donor was the Sanborn family, the children and heirs of the late preacher. The public now deserves to know why this precious archive was sequestered for fifty years after Edward Hopper’s death by a family that had no relationship to the artist. The family still possesses at least another thousand documents and early art works, some of which they have loaned (but not donated) to the Hopper House, a local art center located in the Hopper family home in Nyack. Others are still available for sale at commercial art galleries. Why such valuable documents could be suppressed from scholarship for so long demands an answer.

The Whitney would have us believe that Edward and Jo Hopper did not intend to include their papers in her bequest of all “works of art.” The Whitney’s press release assumes that it is the most natural thing in the world for these artists’ original written materials to turn up in the possession of a local Baptist preacher, who happened to dwell near the Hopper family home, where Edward’s spinster sister, Marion, died not long before her brother’s death. The Whitney cannot explain how and why said clergyman also got hold of so many of Hopper’s oil paintings, watercolors, and illustrations, as well as hundreds of Hopper’s drawings, all of which were by destined for the museum by Jo Hopper’s will; nor why the preacher suppressed most of these documents until his death in 2007; nor why his heirs, the Sanborn family, continued to hide these documents for another decade, impeding basic scholarship on Edward Hopper.

Fortunately, Arthayer R. Sanborn himself, explained how he formed much of his “Hopper Collection” in a recorded public lecture that he gave at the Rockland County Historical Society in New City New York on July 21, 1982, on the hundredth anniversary of Edward Hopper’s birth. I did not attend because in the years before the internet, I knew nothing of its happening. But the Rockland County Historical Society years ago sent me a tape of this public lecture, which I have now had digitized. I have placed copies in many archives of universities and art museums to insure its preservation. It is available in full on SoundCloud and immediately below is a separate excerpt of the most incriminating passages.

When I began my research on Hopper at the Whitney, I had no idea what my diligence would uncover. Nor did I understand how my discoveries would make me a “whistle blower,” exposing theft, corruption, as well as the Whitney’s shame in discarding and destroying much of the art of Edward’s wife, Jo (all of her stretched canvases and some of her best framed watercolors). I found myself up against traditional male chauvinism, perpetuated and compounded by self-serving interests of art world powers. Indeed, even the concept of a “whistle blower” was then unknown to me, yet my professional training as an art historian dictated that I gather information and reconstruct situations, letting proverbial chips fall where they might. Revering the museum as a public institution, I felt it my duty as a curator to protect the public’s interest and to alert my employer to the preacher’s fraud. Instead of thanking me for exposing a thief, the museum fired me in a manner as humiliating as possible, trying to quiet the case and sweep the scandal under the rug.

Although some might imagine that working as a curator in a major museum was a dream job for a young scholar, my employment turned into a nightmare. All these years later, I feel grateful to have survived, to have had an alternative career in art history as a professor and writer, and finally be able to tell this story, presenting ample documentary evidence on this website. For me, however, being forced to act like a sleuth in a detective novel and unmask the canny thief, has been both challenging and stressful. Instead of praise from the Whitney, I found what I would later come to understand as connivance by the museum and miscellaneous art world crooks, including art dealers and auction houses. Because of the statute of limitations, it’s now too late for these crooks to be tried in court. Nonetheless, the guilty should still be convicted in the courtroom of public opinion. Such corruption in public institutions should never again be allowed. All artists should take action to protect their estates from such criminal opportunists as “Reverend Arthayer R. Sanborn.

It would be easy enough for me to post on a website many of the works stolen from the Hopper estate. By doing so, however, I would provide a kind of informal “authentication” for the illicit market. Neither galleries nor auction houses, nor indeed museums, winked at by the Whitney, have shown any will to stop the buying and selling of art stolen from the Hopper estate. Forgers, moreover, have spotted opportunity. Fakes, pretending to be by Edward Hopper, now pollute the market. A forger need only pretend to have a Sanborn provenance! Thus, I have refrained from illustrating on this site most of the questionable works, whether stolen or forged; but they are numerous. Anyone that contemplates the purchase of Edward Hopper’s “early works” (including those in my catalogue raisonné), “preparatory sketches,” and paintings not in my catalogue raisonné, should consider if they wish to connive in one of the largest art frauds in American art history. This is definitely not what Edward Hopper or Jo Hopper intended when they willed their artistic estates to Mrs. Whitney’s museum.