Sanborn, to cover up and justify his theft from the Hopper estate, created an entire persona, a fictional public identity, something like a theatrical mask. From man of the cloth, he took early retirement and reinvented himself as an expert devoted to the art and life of Edward Hopper.

Arthayer R. Sanborn, the preacher who stole art from the home of his congregant, Edward Hopper’s sister, Marion, who lived in the house until her death in 1965.

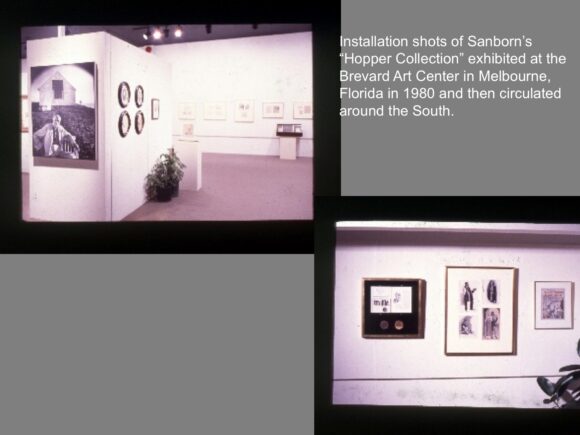

He contrived a fictive narrative to compete with what I was doing as the curator of the Hopper Collection at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1980, to match the retrospective show that I curated for the Whitney, he went so far as to stage a show for the museum in his new hometown of Melbourne, Florida, presenting his “Hopper collection.”

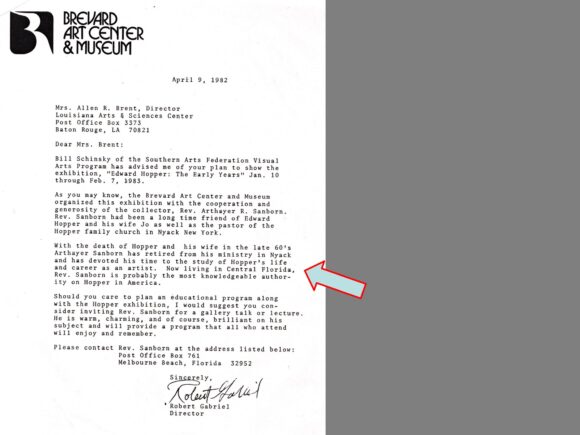

His catalogue essay for the Florida show develops a counter-narrative. When the Brevard Art Center’s director, Robert Gabriel, attempted to tour the show, he wrote on April 9, 1982, identifying Sanborn as “probably the most knowledgeable authority on Hopper in America.”

Capitalizing on the cliché that small towns take exceptional pride in native sons, Sanborn exploited what he had learned from his tenure in Nyack, as he drew on his purloined archive to forge his own personal link to the history of the Hopper family. In their attic, he had come upon what he described, in an unguarded moment, as “the trove” of Hopper family papers. Exploiting that pilfered archive, the preacher set out to corner the market on the ancestral history of the Hoppers, which he was able to do because he had taken all the documents and works of art that the family had saved for generations, material very surely intended for the Whitney in Jo’s very specific bequest. Not only did he keep the trove hidden, but in 1972, when he took early retirement and left the area, he maintained some connections and ultimately helped to instill pride among Nyack citizens in their native son, even though Edward Hopper had long since rejected Nyack.

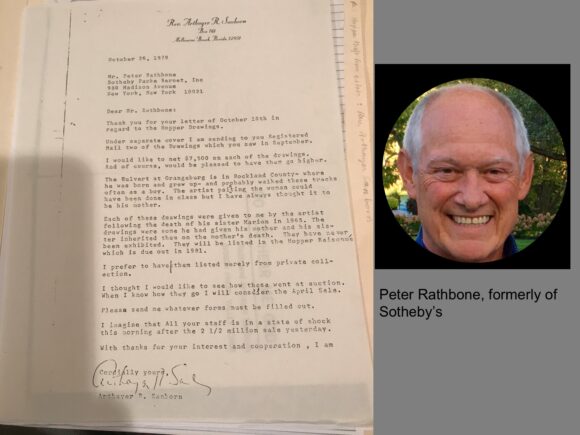

The preacher orchestrated his activities with calculation and care in order to cover up his true intention and motivation, which was to create cover for his criminal dealing—selling stolen art for which he had no documentation. In the beginning, he sold at auction and to commercial galleries and private dealers, artworks by Edward Hopper that he had stolen. From the sellers, he required that his name not be revealed, as is documented in this letter below that he wrote to Sotheby’s in 1979.

At the same time, he schemed to make it look like it was reasonable for him to have possession of so much of the Hopper family’s art and archives. Thus, he began to portray himself as a Hopper family intimate.

It was relatively early in his game, when he presented himself at the door of my Whitney museum office. His personal manner and demeanor reminded me of Charles Dickens’ Reverend Mr. Chadband, the hypocritical clergyman in his 1852 novel, Bleak House. Both preachers loved the sound of their own voices. Each spoke in bravuras and flourishes. Sanborn’s florid style made him seem greasy and insincere. This was true in both his conversations with me and in his public performances. Listen to him speak in his public talk presented on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Edward Hopper’s birth on July 22, 1982, when he told about taking art and documents from the Hoppers’ attic. It is available in full on SoundCloud: Part I here, Part II here.

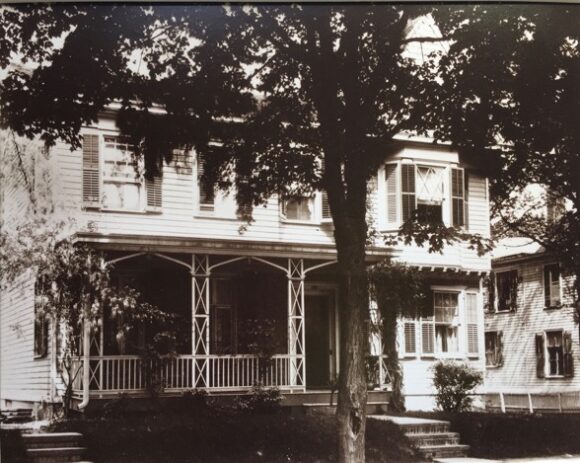

The Hopper family home in Nyack, New York, where Edward and Marion grew up and Marion lived until her death in 1965. The attic with the “treasure trove” is on the upper right.

As impressions grew, the preacher came also to remind me of the stereotypical confidence man operating a game of manipulation. Practiced in his church, he knew just how to play upon people’s gullibility, whether in religion or about secular matters. Just as preachers before him, he aimed at a person’s shame, superstition, or, as he himself so aptly put it, “greed.” There can be no doubt of the rhetorical gifts that he now used– not to stir his congregation to devotion or generosity toward others or to the church– but to mystify the public, so that they should accept the preposterous story that he was Edward Hopper’s old friend.

This aspect of the preacher’s personality calls to mind the character of the Pardoner in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tale. The difference is that this modern-day preacher was not after indulgences or having folks pay some penance for their sins, but rather sought to delude those around him in order to cover up his own sins, namely the theft of property from the Hopper estate. Since the Hoppers were all childless, the preacher probably justified his theft with the thought that his large needy family had far better use for the profits from the sale of Hopper’s art than the Whitney Museum. The museum, however, was not only a tax-exempt public institution, but represented both the public’s interest and the Hoppers’ will. The preacher must have convinced himself that the neither the Hoppers’ will nor the public really mattered.

Like Chaucer’s Pardoner, Sanborn was psychologically astute. This is most apparent when listening to him speak. We can learn about his methods from analyzing the recording that exists of at least one of his public performances (at the Rockland County Historical Society in New City, New York, on July 22, 1982). Entitled “A Reminiscence,” this public talk was on the occasion of the show, “Edward Hopper: His Rockland Heritage and Legacy.” Ralph Sessions, President of the Historical Society, referred to the preacher as “a family friend of the Hoppers.” Then Dorothy Hope, then President of the Hopper House Art Center in Nyack, introduced the preacher as an “old friend of Edward Hopper’s.” He took this untruth as an opportunity to tell his audience that he wanted to correct a few things. He engagingly played on being called “old,” saying that he was not of the Hoppers’ vintage. He said that he had driven North from his Florida retirement to come back to Rockland County, even though had to give up “beaching every day.”

In her introduction to the preacher, Dorothy Hope gave a history of the Hopper house. She made clear that the house remained vacant for two years, until purchased by Juanita Linnet in 1970, who did not occupy the house. A fire occurred on July 8, 1970, which prompted a neighbor to write to the paper to encourage a group to form to save the house, which led to the foundation of the current art center. Mrs. Hope went on to explain how the committee came together to organize and restore this old house and turn it into the center, which opened on April 13, 1975. The opening show was of Edward Dahlberg, since the house owned no works by Edward Hopper. She reviewed the foundation’s aims to have local activities, community arts events, “with a possibility with acquiring Edward Hopper’s work in later years.” That ambition would cause the Hopper House board to ignore the circumstances of how the preacher had come into his collection. Neither the preacher nor his family have yet given the house anything, but they have repeatedly made loans of works of art and documents. The family, in effect, by lending and not giving anything, holds the Hopper house hostage to the myth the preacher concocted.

The preacher then spoke as, “an old friend of the Hopper family.” He chose to explain how he, not Mrs. Linnet bought the contents of the Hopper house. “We moved everything out of that house. She was suing the estate. She could never pay the mortgage.” I “bought the contents of the Hopper house: I paid the bill. The church benefitted.” Were this all true and not a cover for his theft, this would be a unique example of the preacher’s charity.

What the preacher glossed over was the conflict that he had with Linnet: “If this woman had not sued the estate, if she had not been greedy. Greed is a terrible waste. If she had agreed to let me have what I wanted at that house.” In fact, he made it appear as if he had made some kind of a deal with the executor, after having removed most of what he wanted from the attic, including works of art clearly left to the Whitney Museum. Evidently neither the executor nor any one at the Whitney paid attention to the contents of the Nyack house at the time of Jo’s death, or even during the extended time when the will was probated. Sanborn practically dared the audience at the Rockland County Historical Society to challenge him by his bold effrontery and hypocrisy. When he called Juanita Linnet “greedy,” he revealed his own avarice. It was a case of the pot calling the kettle black.

The preacher went on to describe how John Zehner at the Rockland Historical Society had asked him for an article about Hopper, but “he had been enjoying life too much.” “And then my conscience or something bothered me” and “so that’s how come this exhibition got started.”” I tried to pull out of file drawers things that you might like seeing.”

He then spoke about how Edward signed his letters from Paris, which were now in his possession. The preacher also got all of Edward’s letters to his sister Marion, although mostly what he showed me were his typed transcripts. He went on: “For generations, people have known nothing about Hopper.” The only reason that anyone knows anything about Edward Hopper is Jo Hopper.” “She’s the interesting part of this whole story.” For years people have been looking at a window. I want us to look through one of Hopper’s windows to see where he was at. He wore hand-me-down clothes. He’d wear his patched jacket for 25 years.”

The preacher then proceeded to go on a diversionary tactic: “Unless there are roots there can be no growth. A tree…the roots were very strong they didn’t run into a stone wall that made the growth die out.” Here he is once again the preacher with a moral message, however unconvincing. “Think what the world would have lost,” he credits himself by claiming, “if someone ditched everything and said that they were of no value.”

The preacher spoke directly about his having had access to the Hopper family home: “Some of the things that were in that attic. The only reason that I went into the attic I had a key when Marion was living there alone. I was the only one who had a key to her house. The only reason that I had a key was so that I could go in and out of my choice without disturbing anyone. I got her a TV to loosen her up and to sweeten her up a little bit.” He got Marion hooked on watching soap operas so much so that she did not want to be disturbed. He was delighted.

He goes on to explain that after Marion’s death, “I took care of the property for Edward and Jo and for the bank of NY while they were the executor.” He might have said, “I took the property…” for that is what he did. He goes on to recount a tale that reminds one of a fox in a hen coop: One day while in the house with his son checking up, he noticed what seemed like a “dead bird.” “We went up this rickety old ladder to the attic. We began looking around. It was a treasure trove—unimaginable—of all vintages. And I of course was particularly interested in the things that he had saved— in all my collections…the bottle they saved everything—there is a nail out of one of the churches that was torn down. This was his first studio.”

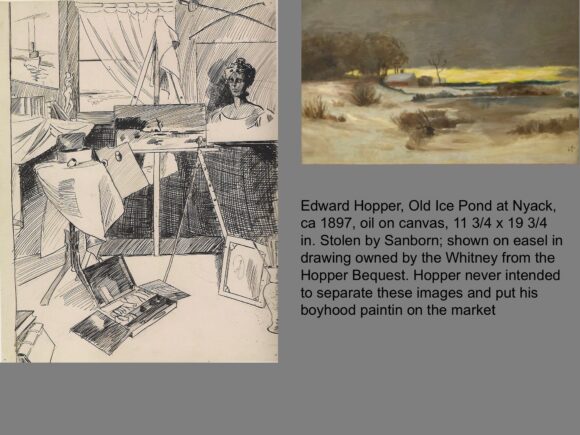

He speaks of a picture in the Hopper bequest of Edward’s first studio in the attic, of a picture on an easel, and goes on to tell “I have this easel at home. I have the picture [that] he painted there on the easel that he painted. This is where the great man started.” He had obviously picked out for himself what he wanted and what he thought that he could get away with.

What the preacher is boasting about in telling of his foray into the Hopper attic is having found and taken possession of Hopper’s early oil painting that is depicted on his easel in an early sketch of his attic studio. The preacher then proudly says that he displays this same picture on Hopper’s original easel, all of which are conveniently in his possession. The main problem with this revelation is that Jo left all works of art by anyone to a public collection, the Whitney Museum. The preacher, however, goes on to speak about a notebook on the TC Club, the three Commodores, made by Edward with some of his friends when he was about fourteen years old. He describes a picture of the boatyard with sketches. The main problem with this revelation is that Jo left all works of art by anyone to a public collection, the Whitney Museum.

The preacher then pivoted into a discussion of the Hopper family’s ancestry. No one could argue with him about that since he had taken possession of all the family documents. What gave him the right to do so? Why did the Whitney, the legatee of the artistic estate, (including all of the art works that were found in the Nyack house) allow this?