Timeline:

1964 January 20: When the Whitney Museum was producing the catalogue for the last retrospective exhibition (1964) held during Edward Hopper’s lifetime, Jo Hopper wrote to Margaret McKellar of the Whitney staff, telling her that Hopper’s mother and she had both been “packrats,” saving everything, even letters sent from the family with which Hopper had stayed as a young man in Paris: “Pack rats might not like to be associated with the Rat Family even, however honorably antiquarian. Of course, I keep everything from way, way back—letters to his mother from French people E. [Edward] stayed with when in Paris to say E. such a very good boy in 1906. His mother gave them to me. She a pack rat too.” Clearly Jo was hinting at what the museum could expect to receive in the future with the Hoppers’ intended bequest.

- Catalogue by Goodrich of Hopper’s retrospective at the Whitney in 1964.

- Lloyd Goodrich: Curator of 1964 Hopper retrospective; dealt with Larry Fleischman and wrote another essay to help launder art stolen by Sanborn.

- Edward and Jo Hopper in Washington Square Park.

The Whitney, however, made no effort to obtain the Hoppers’ papers to which the opportunist, Arthayer R. Sanborn, helped himself. He and his heirs sequestered more than 4,000 of these documents for fifty years after Edward Hopper’s death, withholding them from the Whitney Museum’s project of a catalogue raisonné, even while manipulating the curator, Gail Levin, to authenticate his collection of stolen art.

- Arthayer R. Sanborn

- Edward Hopper: Catalogue Raisonne by Gail Levin, published in 1995 by W.W. Norton & Co. for the Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Gail Levin ca 1979, as a young curator at the Whitney Museum, working on the Edward Hopper Catalogue Raisonne

1964 Whitney Museum holds the last retrospective of Hopper’s work during his lifetime, organized by the director, Lloyd Goodrich, a longtime supporter of his work. Hopper wrote a letter on September 14, 1964, to his sister Marion just before the opening of his Whitney retrospective, telling her that she cannot bring “Dr. [Arthayer] Sanborn and Beatrice [Acken],” two of her friends from the church, because he has “no time” for her or them. This is not the evidence of the close friendship Sanborn pretended to have had with Edward Hopper. (see Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, p. 565.)

1965 July 4, Edward Hopper and Jo Hopper are driven from New York City up to Nyack by the local preacher, Arthayer R. Sanborn, who picked them up in Edward’s automobile, that he stored at the Hopper family home in Nyack, where he grew up. Edward’s only sibling, Marion Louise Hopper, who still lived there, was failing and Edward and Jo had to fill in for her housekeeper, who had departed for the holiday weekend. Marion (August 8, 1880-July 17, 1965) entered the hospital on July 16 and died the next day. She had long since given the key to the Hopper family home, where she and Edward Hopper grew up, to Rev. Arthayer R. Sanborn, Jr., the preacher at the local Baptist church that Marion attended and Edward shunned.

- Edward Hopper with his sister Marion Hopper– the two children who grew up in the Nyack, New York house.

- Hopper family home in Nyack, New York, where Edward and Marion grew up and Marion lived until her death in 1965.

- Marion Hopper attended the Baptist Church in Nyack, New York, where Sanborn preached.

Sanborn later told in a public lecture (July 22, 1982) (listen to this on audio recording below) how he felt about Marion and how he got a television set “to sweeten her up.” Once Sanborn got her hooked on soap operas, she did not want to be disturbed when he came to check on her, so she gave him a key. Sanborn tells how he kept the key after the death of Marion, Edward, and then Jo. He virtually documents how he stole so much art out of the Nyack attic.

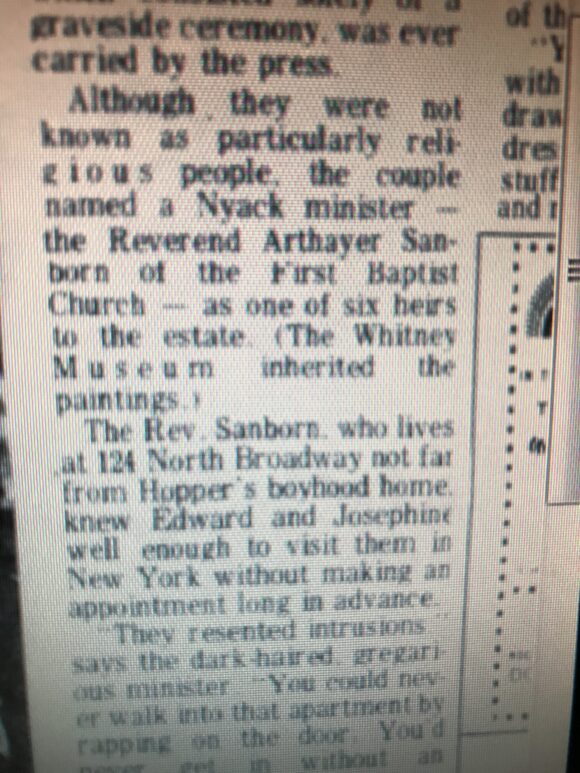

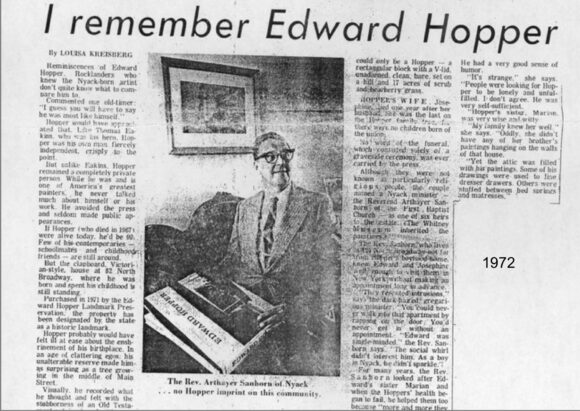

1967 Edward Hopper (born July 22, 1882, Nyack, N.Y., U.S.—died May 15, 1967, in New York City). He left his estate entirely to his wife Josephine Verstille Nivison Hopper, known as Jo. Sanborn was not mentioned in his will, contrary to what he told at least one journalist, Louisa Kriesberg, who interviewed Sanborn in 1972 for a feature in the local Nyack newspaper, the Journal-News, called “I remember Edward Hopper,” reported, “Although they were not known as particularly religious people, the couple [Edward and Jo Hopper] named a Nyack minister—the Reverend Arthayer Sanborn of the First Baptist Church as one of six heirs to the estate. (The Whitney Museum inherited the paintings.)” [See clipping of 1972 article.]

Detail of April 9, 1972 article in which Sanborn claimed that he was named in Edward Hopper’s will, which he was not!

April 9, 1972 article in the Journal-Record of White Plains, NY in which Louisa Kreisberg interviewed Sanborn, who falsely claimed to have been named in Edward Hopper’s will.

1967 Eddy Brady, the superintendent of the building where the Hoppers lived on the top floor at 3 Washington Square North, was most helpful and essential, even doing Jo’s shopping for food and necessities. She was neglected by nearly everyone else including the Whitney, but Sanborn was on the spot.

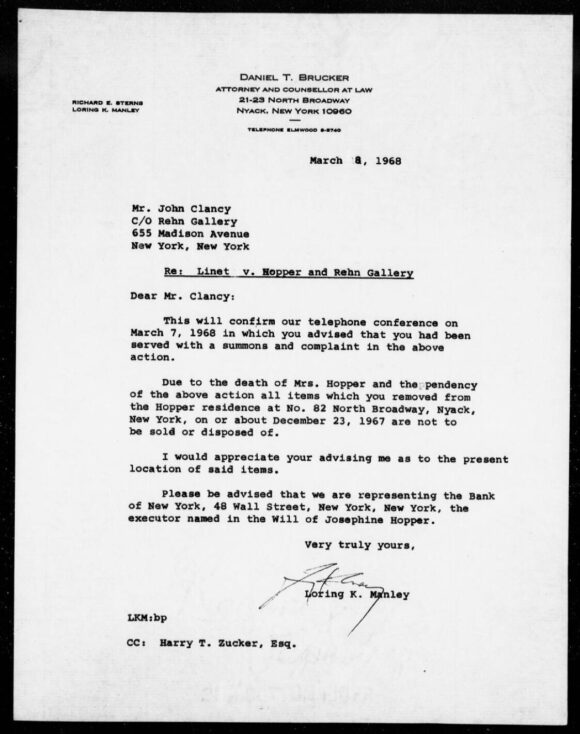

1967 Rehn Gallery files at the Archives of American Art document that Sanborn was in the Nyack attic in December, after Edward’s death, but while Jo was still alive. She was far too sick to visit Nyack. He had a list of pictures given to Jo by Edward that had to be retrieved (since they were not to be taxed.) The executor of Edward’s estate asked Sanborn to get these pictures out of the Nyack attic.

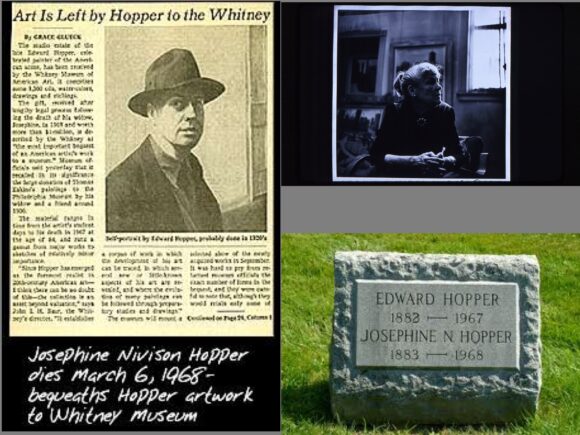

1968 Edward Hopper’s widow, Josephine “Jo” Nivison Hopper (born New York City 1883–died on March 6, 1968, twelve days before her 85th birthday, in NYC), surviving less than ten months after she lost Edward.

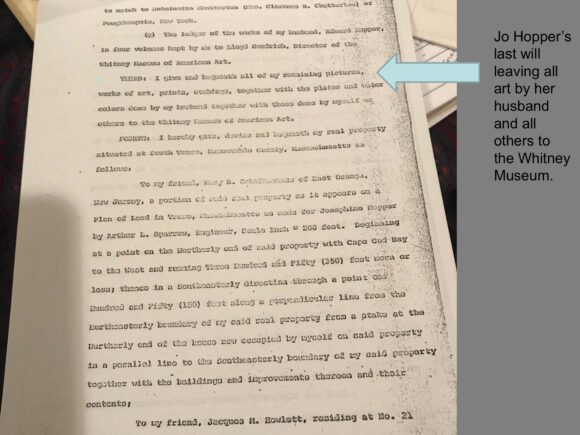

Jo’s last will, signed on September 1, 1967, after Edward’s death and just six months before her own death, made the bequest of two specific paintings by her, one to a friend and another to a public library on Cape Cod, where the Hoppers spent half of every year. And she gave one folk painting to the Metropolitan Museum. But Edward’s art—all of it, she gave to the Whitney, along with all other works of art that they owned, no matter who made them.

Sanborn persuaded Jo to add him to her last will, signed after Edward’s death, just months before she died, but, she left him no art works at all. She left all of Edward’s art to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Yet Sanborn possessed a huge number of art works, the transfer of which is undocumented despite Jo’s careful recording of gifts in the record book.

Sanborn had gotten Jo to add him as the last of six residual beneficiaries, after Edward’s death, since he was not mentioned at all in Edward’s will. During the last few months of Jo’s life, Sanborn still had the key to the uninhabited Nyack House as per his own recorded public lecture at the Rockland County Historical Society on July 22, 1982. He stole hundreds of art works worth millions of dollars in today’s market. The heirs to the Arthayer R. Sanborn estate are still selling Hopper’s art for which there are no documents of transfer, because these works were stolen.

1969 March 19/20: Study for Hopper’s award-winning poster, Smash the Hun of 1918 is sold at Parke-Bernet as lot number 3 for $4,000. Sanborn got most of Hopper’s printed illustrations and other related art from the attic and knew what he was taking. Hopper would have wanted the study for his early prize to go to the Whitney with his collection. He would never have given this unique work away, especially to someone who would put it up at auction.

Study for Hopper’s award-winning poster, Smash the Hun of 1918 is sold at Parke-Bernet as lot number 3 for $4,000. This is one of the earliest instances of Sanborn’s selling art he took from the Nyack attic.

1970 According to Philip Sanborn, Arthayer’s son: When Mrs. Hopper died, Arthayer Sanborn continued to look after the property for the estate until 1970, when the house and its contents were sold to Juanita Linet. [New York Times 2012]. Sanborn told in his public lecture in July 1982 how he wanted certain things from the house, but claimed that Mrs. Linet was too greedy, so he stopped the sale and bought the contents for himself. As a residual beneficiary, if he found any art works, he knew from Jo’s will that they belonged to the Whitney Museum! How indeed could the executor have given to only one of the six residual beneficiaries special purchase rights conflicting with the terms of the will, and excluding the other residual beneficiaries?

The New York Times, 2012: “Arthayer Sanborn spoke of the lawsuit at a 1982 celebration of Hopper’s 100th birthday. He said that he had asked Ms. Linet for a few “meager things” from the house, and that she had refused. Then, because he had an unspecified “paper that Mrs. Hopper had signed,” he said he was given permission by the estate to buy the contents of the house.”

Philip Sanborn to Robin Pogrebin, reporter of the New York Times: “So, in keeping with his hope that Hopper family history would be preserved, my Dad purchased the contents of the house, lock, stock and barrel. The contents consisted of glassware, dishes, kitchen utensils, bathroom contents, family mementos, letters, photographs, furniture, old clothes, some early sketches and drawings, etc. There was no definition or exclusion in what was meant by ‘contents.’”

Note: There is no legal way that the executor could sell the contents with artworks left to the Whitney to Sanborn, just one of the several residual beneficiaries of Jo’s will. One can also argue that vintage family photographs were art works, but there is no question about “early sketches and drawings” by anyone, but especially by Edward Hopper. These were clearly left to the Whitney in Jo’s will. If someone, an attorney or a lawyer breaks the law (which I do not believe Philip Sanborn’s claims that they did), it still would not make this “sale” to Sanborn legal. He knew the will well! The childrens’ jingle: “Finders Keepers losers weepers” is not law.

1970 John Clancy successor as Hopper’s dealer at the Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery in New York sells Hopper’s early Monhegan Landscape, Gull Rocks (#CR O-206) to Bernard Dannenberg Galleries in New York. Hopper did not enter this work in his record books nor did he ever sell any works from his Monhegan trips. Either the Whitney Museum had no knowledge of such sales or did not care.

Edward Hopper, Monhegan Landscape (Gull Rocks), 1916-19. Oil on board, 12 x 16 1/4 inches (30 .5 x 41.3 cm), signed lower left: E. Hopper. Sold anonymously after Sanborn removed multiple art works from the Nyack attic. Present whereabouts unknown.

1970 January 29 at Sotheby Parke-Bernet, lot #154, Harbor Scene, 1899, is sold as “provenance of the artist,” for $2500, but Hopper neither sold, showed, or gave away his juvenalia, all of which had to have come from the Nyack attic. Either the Whitney Museum paid no attention to such public sales or did not care.

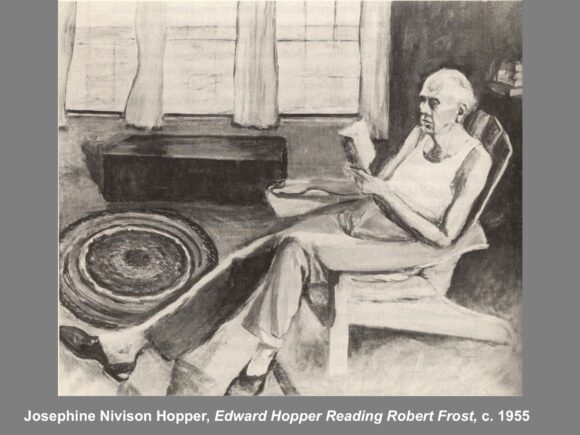

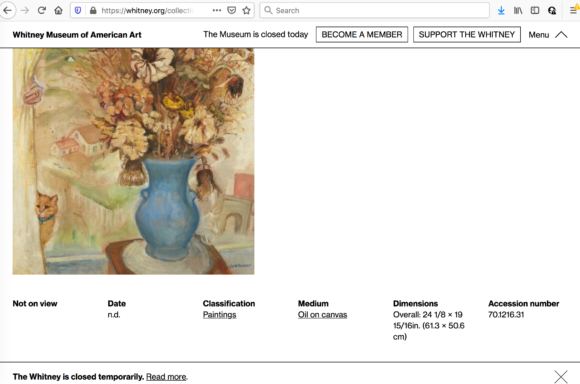

1970 The Whitney discards all of the framed works and stretched canvases by Jo Hopper that were included in her bequest to the museum. These works were never accessioned. Her oil on canvas measuring 24 x 20 inches, called Obituary, dated 1948, was given as one of 36 works to Lincoln Hospital in The Bronx.

Recently the Whitney recovered this painting from an artist who bought it in a flea market after someone took it from Lincoln Hospital. The Whitney has put this picture on its website with an accession number indicating that it was accessioned by the museum in 1970, which is not true.

This is a false narrative or a lie or whatever you want to call it! Much of Jo’s art (all of her stretched canvases) had already been discarded and destroyed when, in 1970–71, groups of feminist activists such as Women Artists for Revolution placed eggs and Tampax on the Whitney staircase to call attention to the absence of women from a show that purported to survey the contemporary American art scene.

This is a false narrative or a lie or whatever you want to call it! Much of Jo’s art (all of her stretched canvases) had already been discarded and destroyed when, in 1970–71, groups of feminist activists such as Women Artists for Revolution placed eggs and Tampax on the Whitney staircase to call attention to the absence of women from a show that purported to survey the contemporary American art scene.

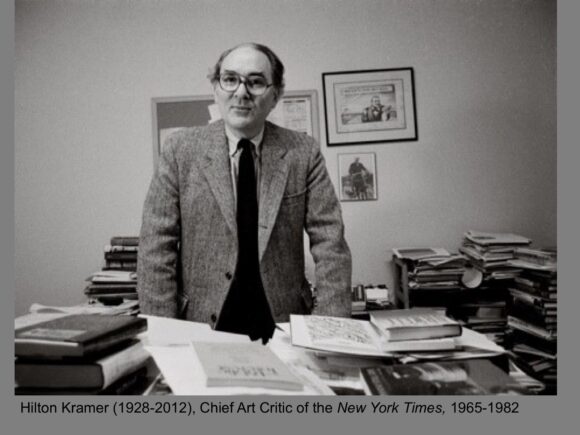

1971 On March 28, 1971, Hilton Kramer, an influential art critic at the New York Times, declared that the Whitney was “Selling a Windfall,” squandering Edward Hopper’s legacy. After defending the importance of Hopper’s art, he wrote: “But if you think that the Hopper bequest means that we shall now have permanent archive at the Whitney where all this material can be studied by the scholars and critics of future generations, you would be guilty of harboring a very old‐fashioned notion of how museums conceive of their responsibilities.” Kramer argued, “The Whitney, it appears, plans to retain only a certain portion of the Hopper bequest for its permanent collection. The rest will be put up for sale on the open market — in gradual stages, of course, in order to keep the (high) price of Hoppers from suffering any precipitous decline.”

HiltonKramer1971HopperBequest1971 December 8: undated nude study is sold for $1300 as lot #11 at Sotheby Parke-Bernet with a photograph inscribed by John Clancy of the Rehn Gallery, but he did not get works like this from Hopper. He was buying from Sanborn.

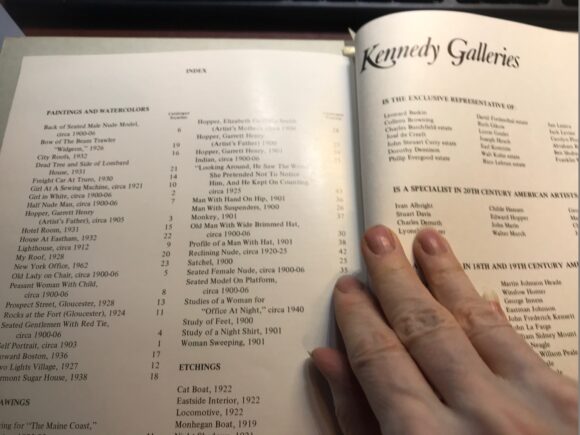

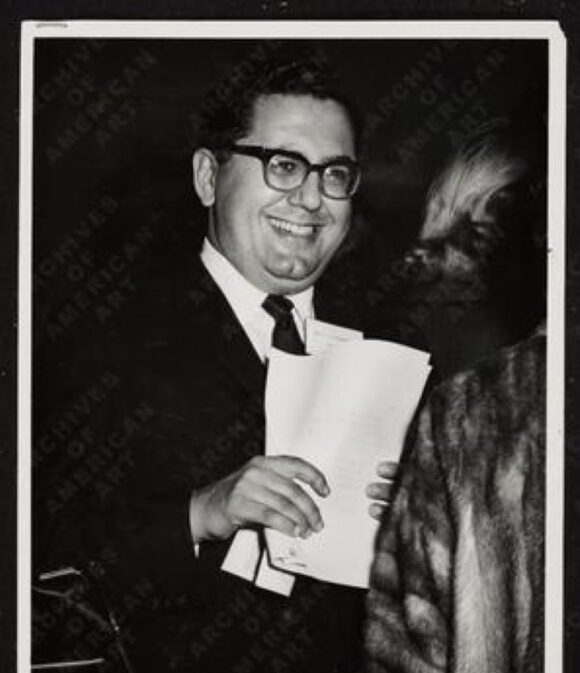

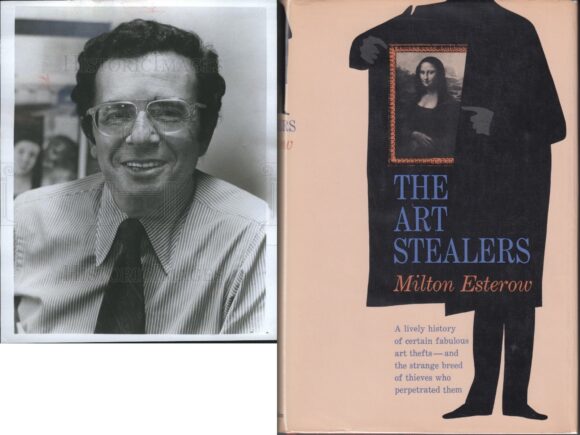

Larry Fleischman, the owner of Kennedy Galleries, Inc. in New York City, who paid Sanborn $65,000 down for a consignment of art works by Edward Hopper that lacked any proof of legitimate transfer. Fleischman proceeded to launder them for the art market.

1972 By early 1972 or sooner, Larry Fleischman of Kennedy Galleries, in New York, paid Sanborn some $65,000 for a large lot of Hopper art works on consignment.

The gallery’s representative who visited Sanborn and gave him the check was Milton Esterow. (Esterow left Kennedy Galleries when he purchased ARTnews magazine in 1972, and then became active as its publisher and editor.) Esterow is the author of a book called The Art Stealers, in which Sanborn would be a perfect example. Sanborn, according to his obit, retired in 1972 and moved to Melbourne Beach, Florida, while continuing to summer in Newport, New Hampshire.

Milton Esterow, who worked for Kennedy Galleries and gave Arthayer Sanborn the down payment for a consignment of stolen works by Edward Hopper. He had authored a 1966 book in which Sanborn would have fit, called The Art Stealers– “A lively history of certain fabulous art thefts– and the strange breed of thieves who perpetuated them.”

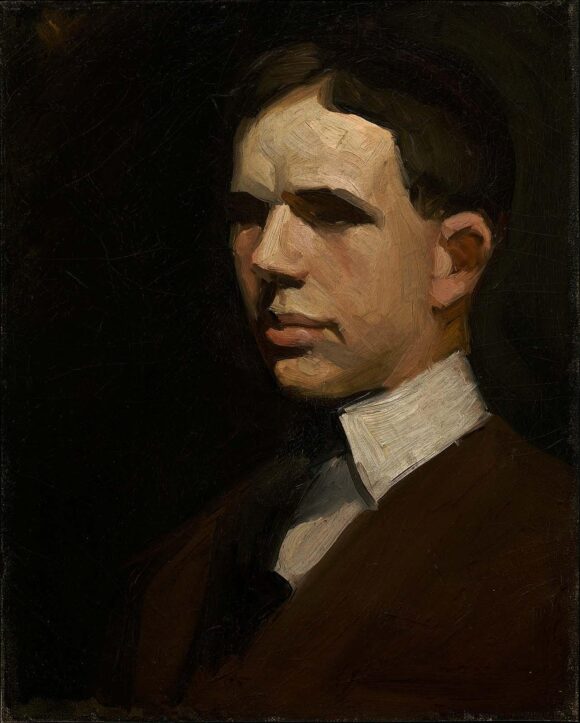

1972 December 13: Sotheby’s Auction of 20th Century American Paintings lot #5 sold for $2100 is Portrait of a Woman, described as “probably painted circa 1900-1906 when Hopper was studying at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri.” Provenance states “Acquired from the artist.” Were this a legitimate sale or gift the above information would not be so vague. There is no instance of such an anonymous portrait of an art school model either being sold or given away. All were in the Nyack attic left to the Whitney Museum. Sanborn had access and was selling at Sotheby’s anonymously during the 1970s.

Edward Hopper, [Portrait of a Girl], 1903-06, oil on canvas, 22 x 18 1/8 inches (55.9 x 46 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

1976 Whitney Museum of American Art acquires a three-year grant of $150,000 from the Andrew Mellon Foundation and hires Gail Levin as the first curator of the Edward Hopper Collection. She is charged with producing a catalogue raisonné, which to document authenticity requires tracing each work by Edward Hopper back through the chain of ownership to his studio.

1976 June 27, Hilton Kramer, in an article, “The Whitney Rediscovers Itself,” outlined in the New York Times the new position and project, noting that Gail Levin would “produce a catalogue raisonné of the entire Hopper oeuvre and organize a major Hopper exhibition to take place in 1980.” After describing the Hopper project as outlined in the museum’s press release, Kramer opined that “The Hopper project is particularly interesting as an index of the Whitney’s new intentions.” (page 29) He then categorized the immense bequest by the artist’s widow as “the largest single gift of its kind the museum had ever received” and reflected that “it seemed at the time to throw the museum into a great state of confusion. It was first announced, and then denied, that the museum would disperse this bequest after selecting a certain number of works for its own permanent collection.” Kramer stated: “Miss Levin’s assignment is important, then, not only to the fate of the Hopper bequest but to the future of the Whitney as a significant repository of American art, and to the museum’s reputation as a place where the standards governing the study of American art will be based on something beyond the seasonal turnover of temporary exhibitions.”

HiltonKramerWhitneyJune27,19761976 days after June 27, Sanborn called Gail Levin and arranged to come to see her at the museum. He arrived deeply tanned and dressed in Bermuda shorts, carrying a large suitcase. He introduced himself as “Reverend Arthayer R. Sanborn.” He told her that he had recently retired as the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Nyack, which Edward Hopper had attended as a boy. He insisted that he had been a friend of Edward Hopper’s.

1976 Sanborn told Gail Levin that the gallery owner, Larry Fleischman, sent Milton Esterow, his employee since early 1969, to Nyack to assess the art works that the preacher was offering to the gallery for sale. Esterow had been a staff reporter on the New York Times. Levin did not know then that he was also the author of the book called The Art Stealers (see above).

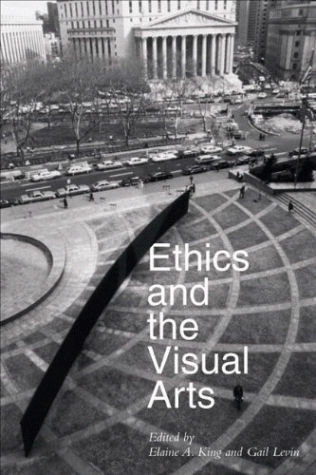

At their first meeting, Sanborn told Levin that as soon as the gallery’s initial check for $65,000 for his consignment of art to be sold cleared, he resigned as pasteur of the Baptist church. Esterow confirmed this account in a letter he sent to Levin in 2006, when she published an article on this matter in an anthology that she co-edited on Ethics and the Visual Arts; Esterow objected only when Levin suggested that he had authenticated the works that he took on consignment from Sanborn, claiming that he had lacked such art historical expertise.

1976 Summer Gail Levin visited Arthayer Sanborn and his wife, Ruth, in both Newport, New Hampshire and Melbourne Beach, Florida, to see Hopper art works for the catalogue raisonné and the exhibitions that she was organizing. Sanborn did not share most of the Hoppers’ papers with her, nor divulge that he had possession of so many. He led her to believe that he showed her all of the Hoppers that he owned; but, it turns out, that he did not. He did not reveal anything about works that he had already sold. Nor did he reveal the extent of his collection of art or of documents from Edward and Jo Hopper, which only come to light in the summer of 2017, fifty years after Edward’s death.

1976 August 20, Museum of Fine Art, Boston writes to the new curator, Gail Levin, asking her if she can authenticate a painting, an early Self-portrait, that they want to purchase from a Rev. William H. Brittain. It later turned out that the painting in question had belonged to Rev. Arthayer R. Sanborn, who told Levin that he gave this valuable painting to his friend. This painting sold to the MFA for $27,500. It appears that Sanborn’s “pal,” Brittain served as a fence to give Sanborn, who did not want to be found out, some cover. At the same time, Brittain also offered to sell the MFA Boston an early drawing of a woman, which they declined to purchase. It too came from the attic of the Nyack house, from Sanborn.

Edward Hopper, Self-portrait, ca 1903, oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 16 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Stolen by Sanborn.

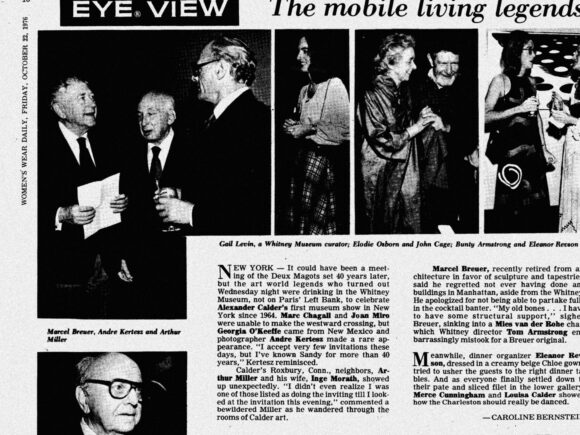

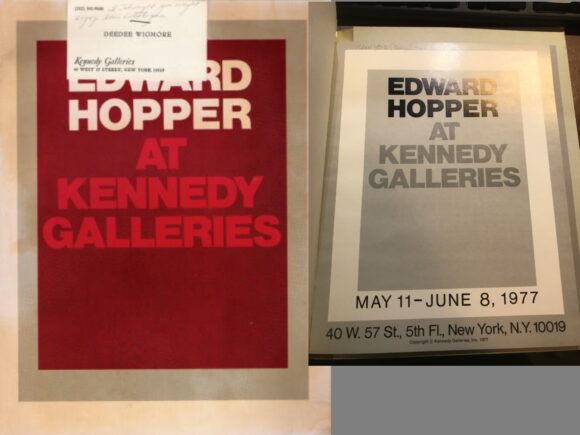

1976 Autumn Tom Armstrong, the Whitney’s director, told Gail Levin, just three months into her employment, that her first writing assignment was to write an essay that would be published in a show of Hopper’s work to be held at Kennedy Galleries. Her essay, for which the gallery paid her $250, in addition to her annual salary at the museum of $16,000, would appear along with one by Lloyd Goodrich, former director of the Whitney, who had curated shows of Hopper and written books about Hopper. It was Levin’s first publication on Hopper. She was thrilled and evidently, Armstrong was thrilled too, for he sent this essay to all of the Whitney’s trustees with a copy to Levin, who still has his note. Why would trustees of a non-profit museum have been pleased to have its curator publish in the catalogue for a commercial gallery? What did they know about Sanborn’s theft and its cover-up by the Whitney?

1977 May 11- June 8. Edward Hopper at Kennedy Galleries opens at 40 West 57th Street in New York City. The catalogue, cleverly conceived by gallery owner, Larry Fleischman, laundered Sanborn’s stolen Hoppers by mixing them with others bought on the legitimate secondary market. No provenance is given in the catalogue, but essays by Lloyd Goodrich and Gail Levin, both of the Whitney Museum, cleanse these works with their murky provenance, making them ready for sale.

Exhibition catalogue from 1977, produced with no provenance, mixing works stolen by Sanborn with others on the resale market

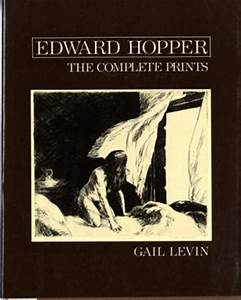

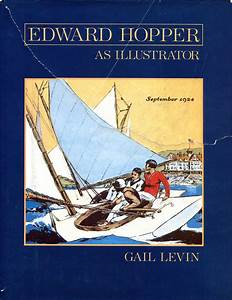

1979 September 27, opening of Edward Hopper: Prints and Illustrations curated by Gail Levin for the Whitney Museum of American Art, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts. She wrote two related books (Edward Hopper: The Complete Prints;

and Edward Hopper as Illustrator, published for the Whitney by W.W. Norton & Co. for the sole profit of the museum and sold as the exhibition catalogues along with a brief free brochure also written by Levin.

This show and book mark the first ever recognition for Hopper’s work as an illustrator and asserted that his work as an illustrator was related to his work as a fine artist. Levin collected Hopper’s illustrations from diverse sources including the Library of Congress, other archives, and Arthayer R. Sanborn. This was the first publication of Hopper’s illustrations as art works since their original appearance in magazines, high school yearbooks, etc., and the first time that all of Hopper’s etchings and their related preparatory drawings were collected and studied. Levin borrowed most of Hopper’s unbound printed commercial illustrations from Sanborn as none of these came to the Whitney, although as art works, they should have been included in Jo’s bequest. In the book on the prints, she wrote: “For information on Nyack and the Hopper family, I appreciate the help of Arthayer R. Sanborn, Maureen Gray, and Alan Gussow.” After showing at the Whitney, the show toured U.S. museums: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, Fort Worth Art Museum, Texas; Milwaukee Art Center, Wisconsin; San Jose Museum of Art, California.

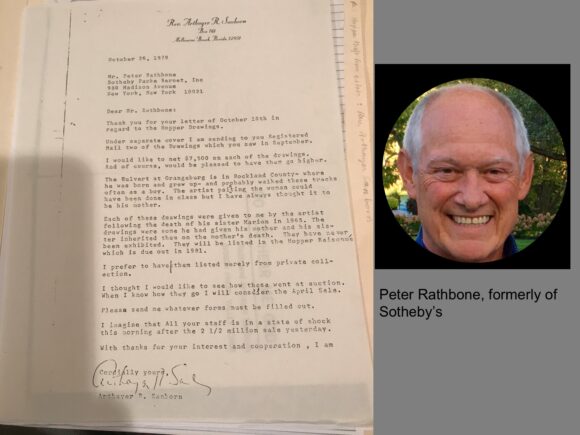

1979 October 26: Sanborn suggested that he was covering up a theft in a letter that he wrote to Peter Rathbone of the auction house, Sotheby’s (then called Sotheby Parke Bernet), saying that he wanted to sell Hopper drawings anonymously from a “private collection,” even though it would have helped to establish authenticity and increase market value if he had urged the claim that the works to sell came from a named “friend” of the artist. Letter given years later by Rathbone to Gail Levin, when he was trying to get from her a statement that a work on resale would be in the catalogue raisonné.

1980 September 24: Christie’s Sale lot #600 for $4,000 Fire Fighting (recto) Male Nude (verso) undated and sold without provenance, but this is an early work that had to have come out of the Nyack attic.

1980 Gail Levin published the first art historical essay on “Josephine Verstille Nivison Hopper” in the first issue of Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring – Summer, 1980), pp. 28-32. This essay reproduces lost works but written while the author was a curator at the Whitney, identifies them as in “private collections,” which could be true, if someone pulled them out of a dumpster or stole them from the New York hospitals where the Whitney had consigned them.

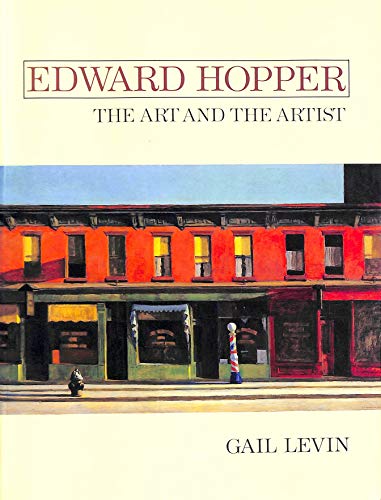

1980 Gail Levin curates Edward Hopper: The Art and the Artist for the Whitney Museum of American Art. A catalogue completely authored by Gail Levin is published by W.W. Norton for the Whitney. It is still in print. Levin traveled to Tokyo and visited Dai Nippon Press to supervise the printing of accurate color. Sanborn referred to Levin’s book as “The Whitney book” in his public lecture at the Rockland Historical Society on July 22, 1982.

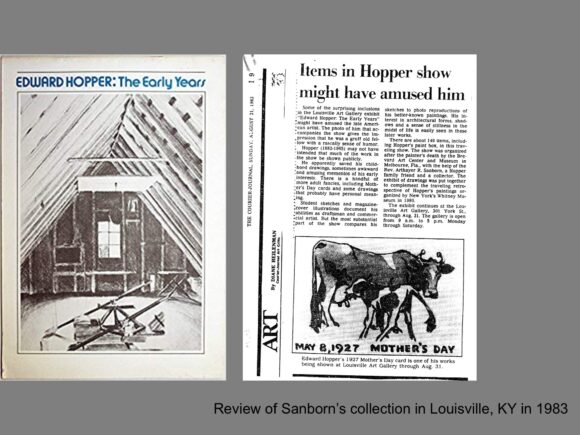

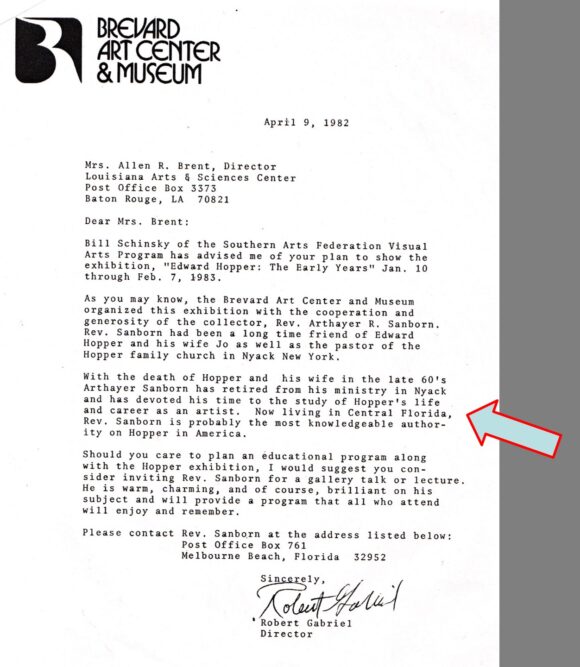

1980 Brevard Art Center and Museum, Melbourne, Florida organizes a circulating exhibition from Sanborn’s collection, “Edward Hopper: The Early Years,” including 3 oils; 2 watercolors; 15 illustrations (1 title unknown); 1 print; 90 drawings. The catalogue contains an essay by Arthayer R. Sanborn.

Toured to Museum of Arts and Sciences, Daytona Beach, Florida, January 9–February 28, 1981 and then to nine more small museums across the South though 1983 (a feature article about the Louisville venue is above).

1981 Edward Hopper: The Art and the Artist tours to the Hayward Gallery under the auspices of the Arts Council of Great Britain; to the Stedlijk Museum in Amsterdam; to the Dusseldorf Kunsthalle in Germany; to the Art Institute of Chicago; and to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

1982 Sanborn began to portray himself as a Hopper family intimate. He began to speak publicly and to have shows of his “collection,” even publishing a catalogue at Brevard Art Center, a small Florida museum in 1980. When the director, Robert Gabriel, attempted to tour the show, he wrote on April 9, 1982, identifying Sanborn as “probably the most knowledgeable authority on Hopper in America.”

1983 Levin reports to Tom Armstrong that she has evidence that Sanborn has stolen his collection from the Hopper estate that was meant to come to the Whitney. She is told to shut up and finish the catalogue raisonné.

1984 Increasingly concerned, Levin reports to Tom Armstrong, the Whitney’s director, that she has amassed more evidence of theft by Sanborn from the Hopper estate. Armstrong, in an attempt to humiliate her, summarily dismissed her and gave her only 30 minutes to vacate the building. This, despite Levin’s stellar record of exhibitions, publications, and reviews.

1984-1995 Levin works without pay to complete the Edward Hopper catalogue raisonné.

1995 The catalogue raisonné of Hopper’s oils, watercolors, and commercial illustrations by Gail Levin was finally published in three volumes and a CD-Rom in 1995, by W. W. Norton & Co. for the Whitney Museum and Schirmer/Mosel Verlag G.M.B.H., Munich, 1995.

These volumes were produced by the Whitney with Levin’s research and writing, but at the museum’s insistence, the provenance for each art work appeared only on the CD-Rom. Using an early pc computer only, the CD is still searchable for all kinds of information such as medium, support, date, but not for provenance or past or present owners, which were never a searchable category. Thus, the fact of the theft was intentionally hidden or at least placed in a manner and location difficult to access. Levin’s repeated notations that a large number works moved from the Hoppers’ estate after their death with “no document of transfer,” were excised before publication. The Whitney made the transfer of each of the works that Levin had identified as coming from Sanborn, all of which were entirely posthumous, look as if they came directly from Hopper, which none did. In later published accounts, Sanborn is falsely identified as “a close friend of Hopper,” which he was not. Levin uncovered a handwritten letter Hopper sent to his sister, telling her that she could not bring Sanborn to his 1964 opening at the Whitney, an event that would be attended by a huge number of people. She maintains a copy of this and other documents consulted.

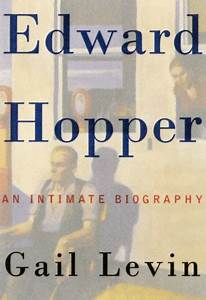

1995 Gail Levin published Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, 1995; University of California paperback; expanded hardcover with 100 new color photographs and 3 new essays by Rizzoli in 2007; as Edward Hopper. Ein Intimes Porträt, Paul List Verlag, Munich, 1998; Edward Hopper Biografia intima by Johan & Levi Editore, Milano in 2009 with translations in Korean 2012 and forthcoming in Chinese). This book published extensive excerpts of Jo Hopper’s diaries, documenting the Hoppers’ close but combative relationship. It is widely read and a basic reference for anyone writing on Hopper. It delves into the literature that Hopper was reading and the films and plays that he and Jo saw and explores how they influenced his art works. Sanborn is mentioned by name, but not identified as the person who walked out with a major painting after visiting Jo in New York after Edward’s death, when she was suffering from loneliness, cataracts, glaucoma, and a broken hip. See page 579: “she continued to keep meticulous track of the whereabouts of her husband’s work, and yet at least one major painting clearly listed as ‘in the studio’ later turned up inexplicably in the hands of someone who in this period took the trouble to face the seventy-four steps.”

1996 Sanborn wrote to Sonny Mehta, publisher at Alfred A. Knopf in March of 1996. He tried to block further publication, asserting to Mehta that he owned or had once owned a list of 29 works reproduced in Gail Levin’s 1995 book, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, to which he claimed copyright. When Knopf’s attorney asked Sanborn for proof of how he came to possess these works, he withdrew his claim in his subsequent letter. Thus, we know that Sanborn had no written documentation to show how he obtained any part of his vast Hopper art collection or he would have produced it when asked to do so by the Random House attorney.

1996 May Arthayer R. Sanborn sends Jim Mairs, editor at W.W. Norton & Co. in charge of Gail Levin’s Edward Hopper: A Catalogue Raisonné, a list of works in oils and watercolors that he claims were “omitted” in this publication. Sanborn, a retired preacher who bills himself as a “Hopper” expert, did not bother contacting the book’s author or getting her opinion. Mairs forwarded this list to her. Some of the works on Sanborn’s list were unsigned and all lack provenance and clear title.

1997 February Gail Levin gives paper, “Feminist Monographs and Jo Nivison Hopper,” at the annual meeting of the College Art Association, New York. She documents publicly the Whitney role in destroying the art of its benefactor. Published in 2003 as Gail Levin, “The Rediscovery of Jo Nivison Hopper,” is published as a chapter in Singular Women: Writing about Forgotten Women Artists, edited by Sarah Webb and Kristin E. Frederickson, published by University of California Press, 2003.

JoHopperSingularWomen20031998 Sanborn and his wife move from Melbourne, Florida to Celebration, Florida.

2006 An anthology, Ethics and the Visual Arts, co-edited by Elaine A. King and Gail Levin was published that includes Levin’s account of how Sanborn got his collection of Hopper’s work, entitled, “Artists’ Estates: When Trust is Betrayed.” After I began to speak out about Sanborn’s theft, lest I be viewed by history as his facilitator, the Whitney began to increase its efforts to block my work as a curator and scholar working on Edward Hopper. As a condition of getting loans, the museum made other museums and curators refuse to work with me, refuse to publish my writing on Hopper, refuse even to have me lecture on Hopper or any other topic.

2007 November 18: Arthayer Sanborn dies in Celebration, Florida, at age 91.

2008 September 14: Ruth Cummings Sanborn, Arthayer’s widow dies in Celebration, Florida, at age 91.

2010 Gail Levin publishes “Art World Power and Women’s Incognito Work: The Case of Edward and Jo Hopper,” in Gender, Sexuality, and Museums: A Routledge Reader, Amy Levin, ed., Routlege Press.

Gender,Sexuality,MuseumsbyLevin2

Gender,Sexuality,MuseumsbyLevin2

2011 Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino publish the best-selling book, Chasing Aphrodite, which recounts Larry Fleischman’s attitude toward stolen art, which lacks good provenance: “Everything comes from somewhere,” Felch and Frammolino quote Fleischman as saying “with a shrug.” What he thought about acquiring stolen antiquities, he also thought about Sanborn’s Hoppers, which he also managed to “launder,” concealing their lack of good provenance. Chasing Aphrodite tells how Fleischman negotiated an exhibition of his and his wife’s collection of ancient art at the Getty, which opened in the fall of 1994.

Under pressure, the Getty had already pledged to stop buying looted antiquities, which broke the UNESCO Convention of 1970. Yet in 1995, the Getty paid the Fleischmans $20 million for 33 works from their collection of ancient art as part of a deal where the couple donated another 288 items to the museum. This is a typical kind of insider deal with a museum, so that the donations cancel out the income tax that the donor would have owed on the sale. The Getty was forced to return some of these antiquities to Italy.

2012 Hopper House Art Center in Nyack names room for Arthayer Sanborn. Gail Levin sends out a press release to protest the naming of a room in the former Hopper house for the thief who stole from the artist’s estate. New York Times investigation into the Sanborn history is conducted by Kevin Flynn and Robin Pogrebin. Whitney refuses access to all documents, claiming the construction of their new building as their excuse. None of these documents have been made available to the press or to scholars.

2016 Gail Levin’s fictional account called “The Preacher Collects,” is published in Lawrence Block, ed. In Sunlight or In Shadow: Stories Inspired by the Paintings of Edward Hopper (New York and London: Pegasus Books, 2016), pp. 155-166.

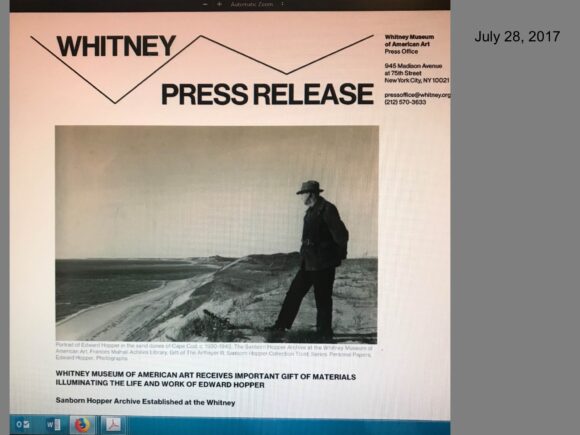

2017 July 29 The Whitney issues a press release announcing the gift of more than 4,000 documents from the Hoppers’ papers by the heirs to Arthayer Sanborn, who has been dead since 2002. No reason is given for the suppression of these papers by people unrelated to Edward Hopper for 50 years after his death. Whitney director Adam Weinberg states matter-of –factly that the materials will be known as “the Sanborn Hopper Archive at the Whitney Museum of American Art,” and that these papers are “the generous gift of the Arthayer R. Sanborn Hopper Collection Trust.”

The 4,000 items include “more than 300 letters and notes from Hopper to his family, friends, and colleagues, twenty-one notebooks in Hopper’s own hand, and ninety notebooks by Hopper’s wife, Josephine Nivison Hopper, as well as extensive archival material relating to Hopper’s artistic career and personal life, such as photographs, personal papers, and dealer records.”

The hiding of Hopper’s papers and the sales of art works that Sanborn purloined can be compared to the plundering of archaeological sites. In fact, the preacher conducted a kind of “clandestine excavation and removal” of Hopper’s art, artifacts, and papers. Much like a robber of tombs in antiquities-rich countries, Sanborn hid and may have manipulated or destroyed some of the historical materials he uncovered. In sequestering his loot for fifty years after Edward Hopper’s death, he kept from scholars the cultural heritage that Edward and Jo Hopper had intended to leave to posterity along with their artistic estate.

The papers given to the Whitney Museum by the Sanborn heirs lacked the “clear title” necessary to put them on the market. I am of the opinion that the Sanborn heirs had no better choice than to give the 4,000 documents to the museum. True, they could have destroyed them or continued to hide them. Instead, they seek to legitimize what their father took, getting the museum to honor their gift as the “Sanborn Hopper Archive.” It will be ironic if the Sanborn “Trust” can take a legal tax deduction against their ill-gotten gains—income from selling art that was stolen in the first place.

2019 The Sanborn Trust continues to hold exhibitions of art works stolen by Sanborn for sale including one that closed in late April at the Heather James Gallery in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. The exhibition and its catalogue is available online. One illustrated letter alone is priced at $30,000. No provenance for any of this stolen art was given.