A stolen Edward Hopper Self-portrait was offered for sale to Museum Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) in 1976 by a preacher friend of the preacher, Arthayer R. Sanborn. It is not conceivable that the thief, Arthayer R. Sanborn, gave away one of his most valuable objects to a “friend,” which is what he told to me when I first met him in 1976. It seems that he used Rev. William H. Brittain to sell the Self-portrait for him: the preacher friend “fenced” this painting for Sanborn. [“The fence acts as a middleman between thieves and the eventual buyers of stolen goods who may not be aware that the goods are stolen. As a verb, the word describes the behavior of the thief in the transaction.”]

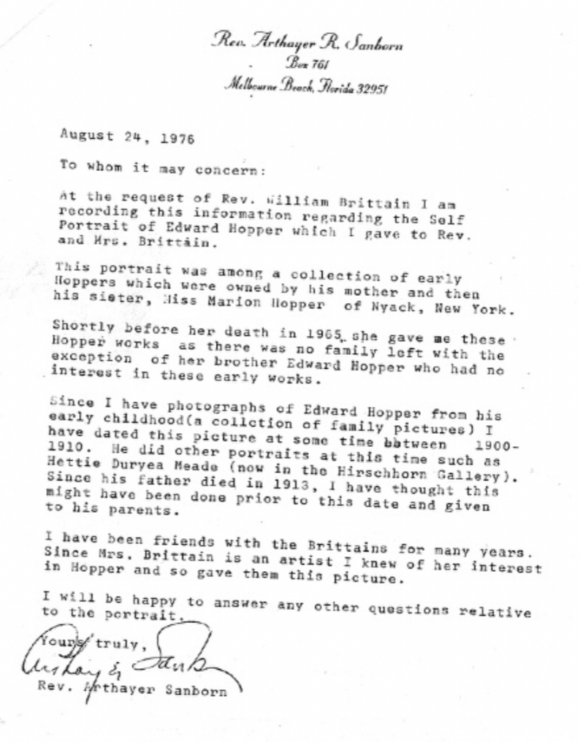

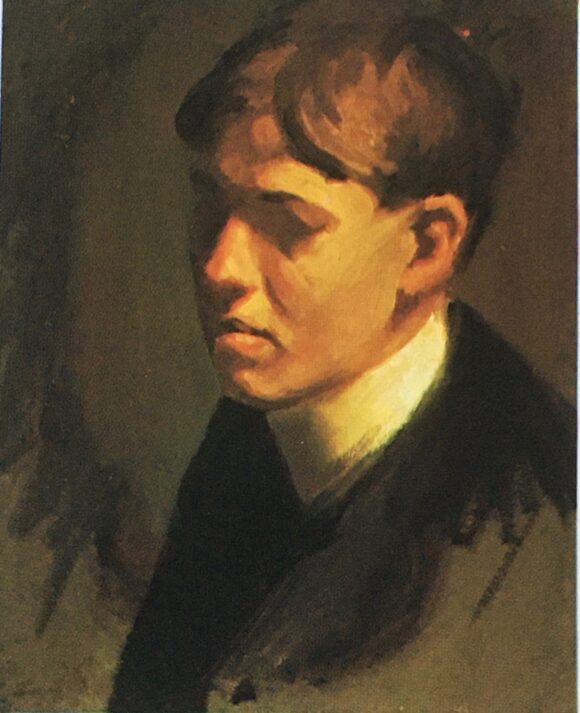

Edward Hopper (1882-1967), Self-Portrait, ca 1903, oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 16 1/4 inches (51.43 x 41.27 cm.) Hayden Collection–Charles Henry Hayden Fund, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. On Reverse: E. HOPPER

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston lists provenance (the history of ownership) for Edward Hopper, Self-Portrait as: The artist; the artist’s mother; to Marion Hopper, Nyack, New York, the artist’s sister; to Rev. Arthayer R. Sanborn; to Rev. and Mrs. William H. Brittain; to MFA, 1976, purchase. [$27,500 was the purchase price].

This is just one example among many of how a naive young museum curator was tricked by the thief, Arthayer R. Sanborn, and collaborating museums and commercial galleries into facilitating an art theft.

June 1, 2019, I visit the archives of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston:

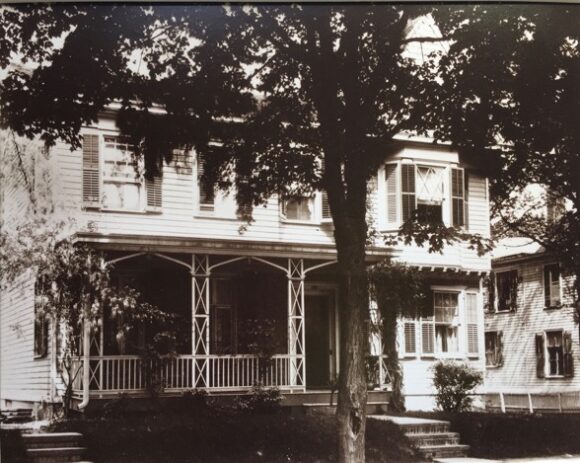

I went to examine the painting files for the early Edward Hopper Self-portrait at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The MFA lists its provenance as Arthayer R. Sanborn, who claimed that it was a gift to him from Edward Hopper’s sister, Marion Hopper (see above). I do not, however, believe this for one minute! There is no proof that this painting even belonged to Marion to give away. It was her brother’s painting, simply stored with others in the family’s house, where she and Edward grew up and she lived until her death on July 17, 1965.

- Edward Hopper with his sister Marion Hopper– the two children who grew up in the Nyack, New York house.

- Arthayer R. Sanborn, the preacher who stole art from the home of his congregant, Edward Hopper’s sister, Marion, who lived in the house until her death in 1965.

Why would Marion have given this valuable painting to Sanborn, whose attitude toward her was so nasty that he disparaged her in a public lecture? Was she completely oblivious to his disdain for her? Or if she was his good friend, why would he give her gift away, when he possessed so many other works by Edward Hopper? Listen to this excerpt of his lecture on this audio recording.

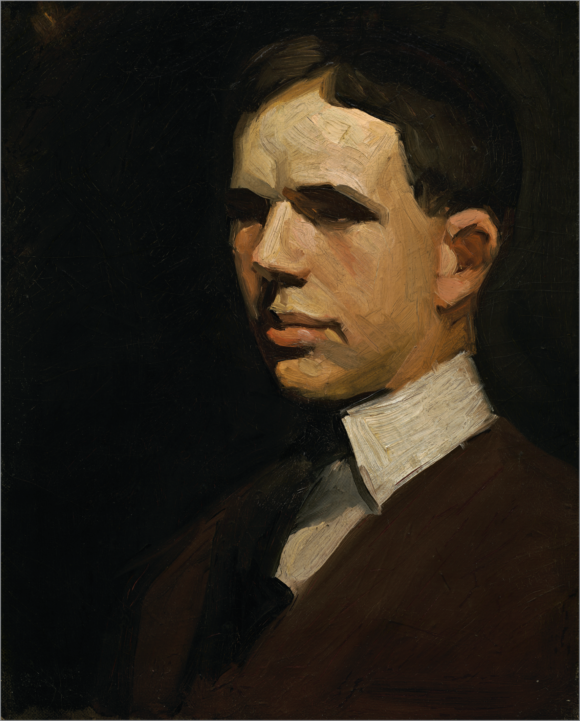

Arthayer R. Sanborn refers in his July 22, 1982 lecture to this catalogue as the “Whitney Book.” Published in 1980, I wrote it and the catalogue raisonne (published in 1995) despite Sanborn’s withholding most of the “more than 4,000 documents” saved by both Edward Hopper and Jo Hopper and by Edward’s family.

This early Self-portrait, now at the MFA, Boston, was one of the most valuable Edward Hopper paintings that Sanborn possessed. (I count among the other most valuable works: the so-called Girl at a Sewing Machine and another early Self-portrait that were purchased from Kennedy Galleries by Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen, and are now in the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, Spain.) The provenance for this Self-Portrait is: Collection of the artist, Nyack, New York (Undocumented transfer to Arthayer R. Sanborn, c. 1965–68); Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1972; Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, 1977. At the time that I researched and wrote the catalogue, Twentieth-century American painting, The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, published in London by Sotheby’s Publications in 1987, I was not yet aware that this painting had passed through Sanborn’s hands. Larry Fleischman, the owner of Kennedy Galleries, was not forthcoming about all of the works he had acquired from Sanborn.

Edward Hopper, Self-portrait, ca 1904, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.6 cm), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

![Edward Hopper, [Girl at a Sewing Machine], ca 1921, oil on canvas, 19 x 18 inches, Museo Thyssen, Madrid.](https://gaillevin.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/1515/files/2020/06/1977.49_muchacha-cosiendo-maquina-580x605.jpg)

Edward Hopper, [Girl at a Sewing Machine], ca 1921, oil on canvas, 19 x 18 inches (48.3 x 46 cm) , Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

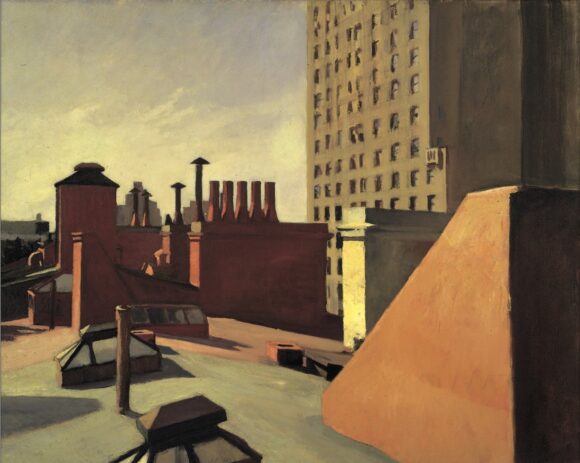

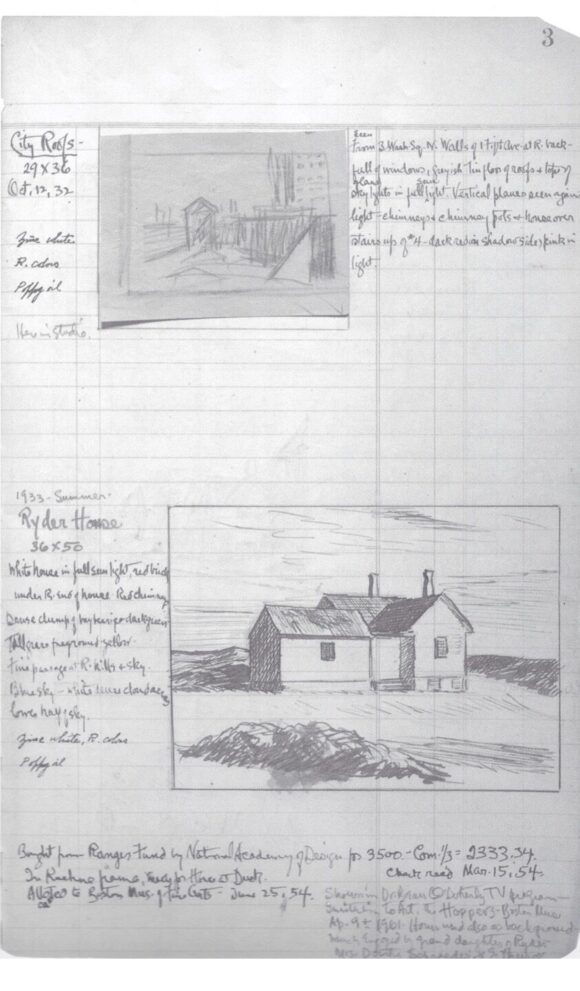

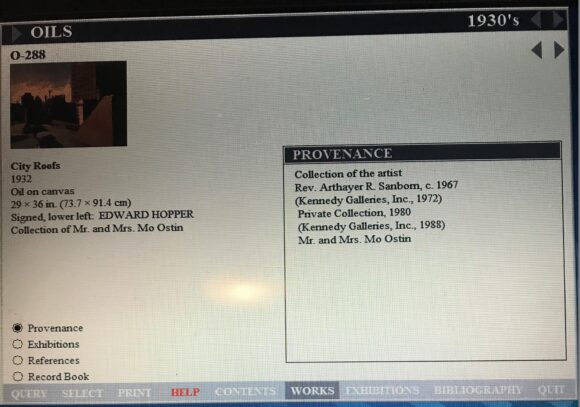

Catalogue Raisonne entry for City Roofs of 1932; provenance is listed only on the CD-Rom. The Whitney Museum of American Art tried to cover up Sanborn’s theft from the estate and edited out my words, “undocumented transfer” from the artist to Sanborn.

Sanborn stole City Roofs from Jo Hopper when he visited her in New York City in the lonely months she lived alone after Edward’s death. She was confined to their apartment due to having broken her hip and her leg. Visually impaired from cataracts complicated by glaucoma, she hobbled around on a walker. Jo recorded City Roofs in the record books she kept as “here in studio” (visible on lower left of image below).

For the Self-portrait reproduced at the beginning of this entry, see also the MFA, Boston website here.

Note: There is no documentation whatsoever to show that Edward gave this painting to his mother or that his sister Marion inherited this painting from their mother. It is not in Hopper’s record books and would simply have been one of his early works stored in the attic of Hopper’s boyhood home in Nyack, New York.

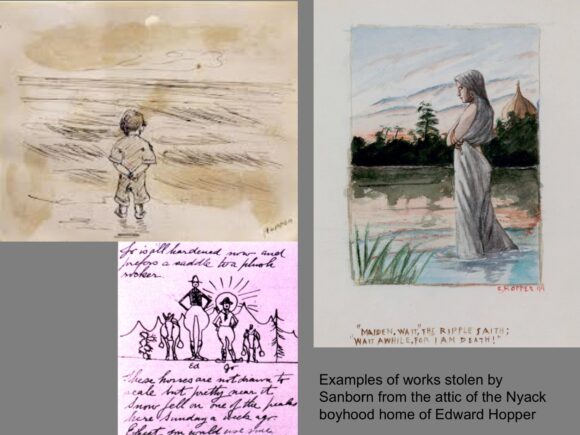

The preacher Arthayer R. Sanborn happened to work at the Baptist Church down the street. He lived nearby and had easy access to Hopper’s only sibling, the aging spinster, Marion Hopper. Posted above, is the July 22, 1982, audio recording of Sanborn, who tells (in a public lecture at the Rockland Historical Society) how he got and kept the key to this house and how he went into the attic and started to assemble his collection:

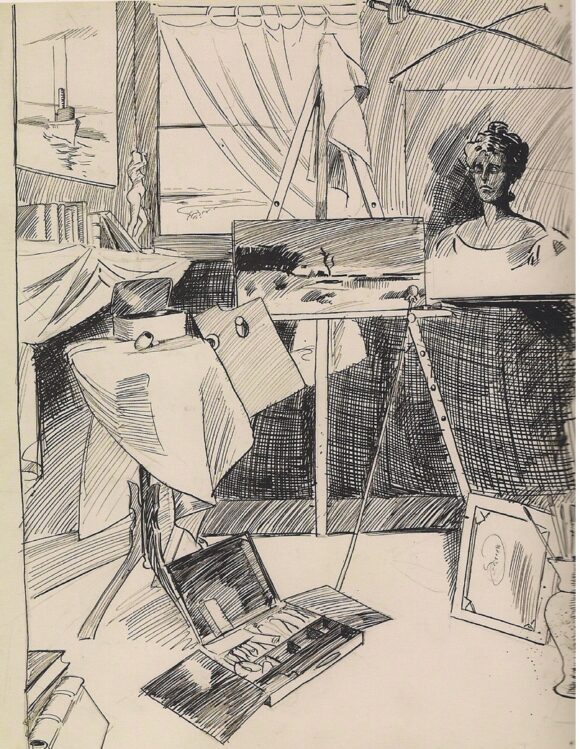

In this drawing in the Whitney Bequest, we see Hopper’s canvas on an easel with a paint box below it. Sanborn boasts in his lecture that he owns all three.

Sanborn speaks specifically about this early oil painting, which he titled, “Old Ice Pond at Nyack.” In the catalogue raisonne, I kept his title and dated it ca 1897. It is an oil on canvas, 11 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches. The painting turns out to be a copy of a landscape by the American painter, Bruce Crane (1857-1937).

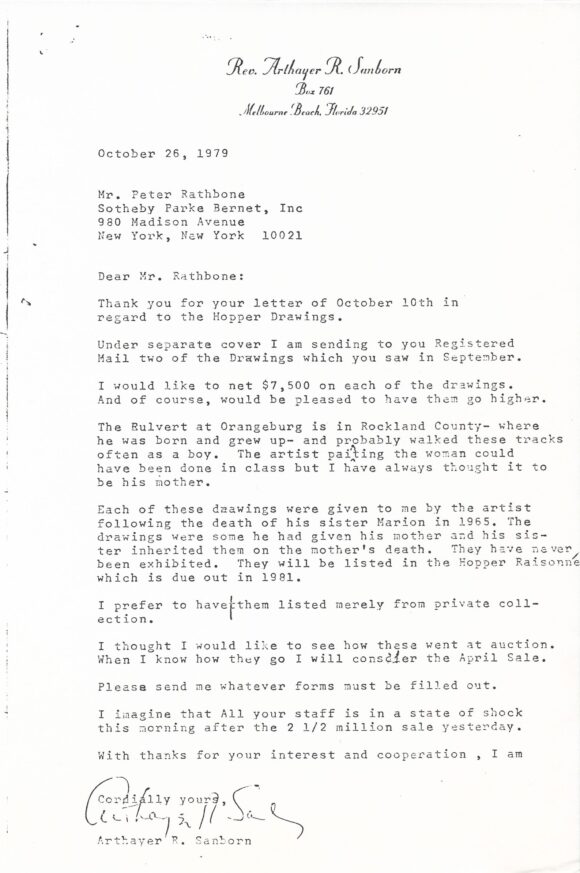

Sanborn told me in person that he “gave” this Self-portrait to his friend, Rev. William H. Brittain, but I don’t believe that now. We now know that (from the letter Sanborn wrote to Peter Rathbone of Sotheby’s in 1979; see it below) Sanborn was selling multiple works by Edward Hopper anonymously.

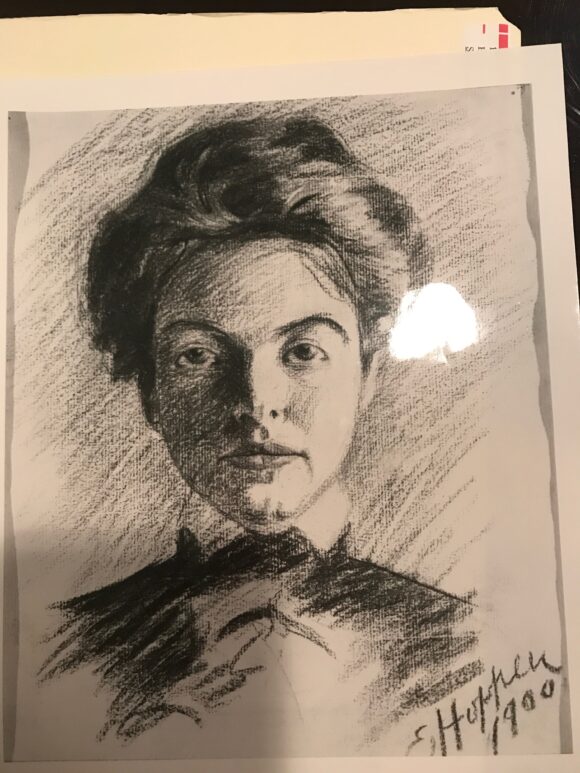

Either Sanborn sold this Self-portrait to an art-collecting preacher friend, or more likely, he had his friend sell this for him, giving him part of the profit. Why would Sanborn “give” away such a valuable object to a friend when he had four children to support, educate, and marry? At the same time, Sanborn’s friend, Rev. Brittain, also offered the museum the opportunity to purchase from him an early Hopper drawing of a woman, which he could have only have acquired from Sanborn, as Hopper never sold these early drawings, nor gave them away. The MFA declined to purchase this drawing.

Cell phone shot of photograph of a 1900 Edward Hopper drawing of a woman also offered for sale by Rev. Brittain to the MFA, Boston at the same time as the Hopper Self-Portrait.

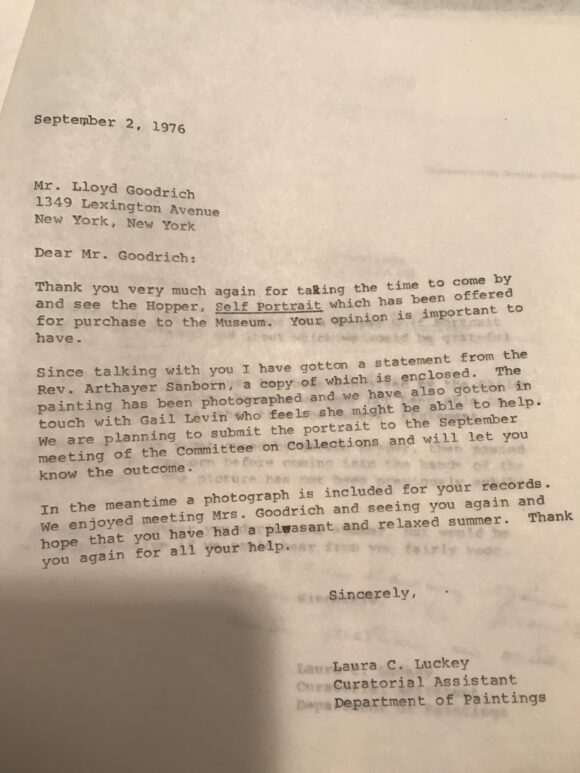

Documents, from the files of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, show what I, still in my twenties and then the new curator of the Hopper Collection at the Whitney Museum, relied upon to authenticate what turns out to have been a stolen early Self-portrait by Edward Hopper. One letter to Lloyd Goodrich (former director of the Whitney Museum and curator of several major Hopper exhibitions) refers to a document giving Arthayer R. Sanborn’s self-proclaimed provenance for the painting, but that document was no longer in the MFA file, when I visited to do my research in June 2018.

The missing document could have been removed and then misplaced only by someone at the MFA with access, authority, knowledge, and involvement, perhaps at the time of organizing the Edward Hopper show in 2007. In 2017, its curator Carol Troyon served as “the expert” who spoke up in the Whitney’s press release announcing the gift of more than 4,000 documents from the Hoppers’ papers (not mentioning their inexplicable suppression for 50 years from Edward Hopper’s death) by Arthayer Sanborn and his heirs.

WHitneySanbornGiftPressReleaseSomeone, to be sure, removed and then misplaced this letter, which I find incriminating. Possibly only after the 2012 New York Times article on Sanborn and theft! I am grateful to the current MFA staff for finding at my request Sanborn’s letter of August 24, 1976 and making it available to me. Among the reasons that I don’t believe the contents of Sanborn’s letter is that Rev. Brittain also offered for sale to the MFA, at the same time as the self-portrait canvas, Hopper’s unrelated drawing of a woman dated 1900. Although the MFA declined to purchase this drawing, the photograph of it remained in the museum’s files and I have reproduced it above. Sanborn declined to comment on the drawing that had been offered at the same time, perhaps because the MFA showed no interest in buying it.

Why do I even care? For one thing, my name is on letters in this MFA file (photographed here with my cell phone as permitted by the museum), signed as the curator of the Hopper Collection at the Whitney [signature redacted]

LevintoLuckey8-20-76So, as a naïve and well-meaning young curator in a new job, I helped authenticate this work for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, so that they could acquire it and Sanborn could get his money. I had no idea then that I was helping a thief! I was only on the job less than three months! Now I want the truth to see the light of day!

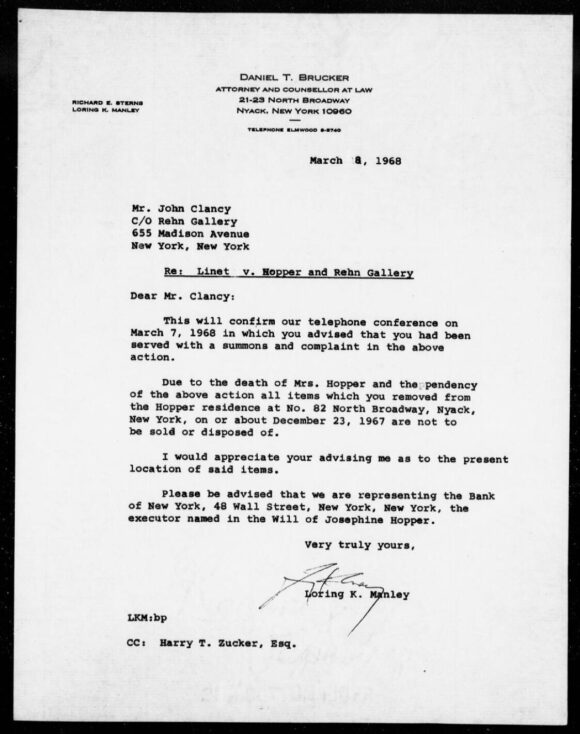

There is a letter in the Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery files at the Archives of American Art (available online): https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/frank-km-rehn-galleries-records-9193

Letter of March 8, 1968 from Loring K. Manley, attorney, to John Clancy, the successor owner of Frank K.H. Rehn Gallery, Hopper’ s dealer since 1924, about the gallery having retrieved Hopper art works for the estate from the Nyack attic; the person with the key who got the works out of the attic was none other than Arthayer R. Sanborn.

This letter documents that by December 1967, Sanborn had gotten into the attic of the Hopper house in Nyack, purportedly to help the executor of Edward’s estate by retrieving the paintings that Edward had given to Jo, who was too crippled and ill to go into the Nyack attic herself. (As confirmed by his son’s recollection to Robin Pogrebin of the New York Times). Sanborn did not take any of these requested paintings that Edward had previously given to Jo, since that would have raised suspicion. Jo wanted them removed because the Executor needed to separate them out for tax purposes. So, we now know that Sanborn had easy access—opportunity— to take art works out of the attic. Despite his claims to the press to the contrary, he did not inherit any art from either Edward or Jo. See this excerpt below from an interview with a 1972 newspaper:

Excerpt from Louisa Kreisberg’s “I Remember Edward Hopper,” published in The Journal News (White Plains, New York) on April 9, 1972, p. 51. Arthayer R. Sanborn told the reporter that Edward and Jo named him as one of six heirs to the estate, but he was only named in Jo’s will, signed after Edward’s death, as one of 6 “residiual legatees.” No art works or any papers by Edward Hopper or Jo were left to Sanborn.

There is no way that Jo would have given Sanborn so many art works without any documentation since she knew, better than anyone else, that art would appear stolen if she did not enter it in the careful record books that she kept. She could and would have listed any such items on the list of gifts to others carefully noted in the record books. Sanborn was simply a cunning thief who seized opportunity (and art) when he saw it.

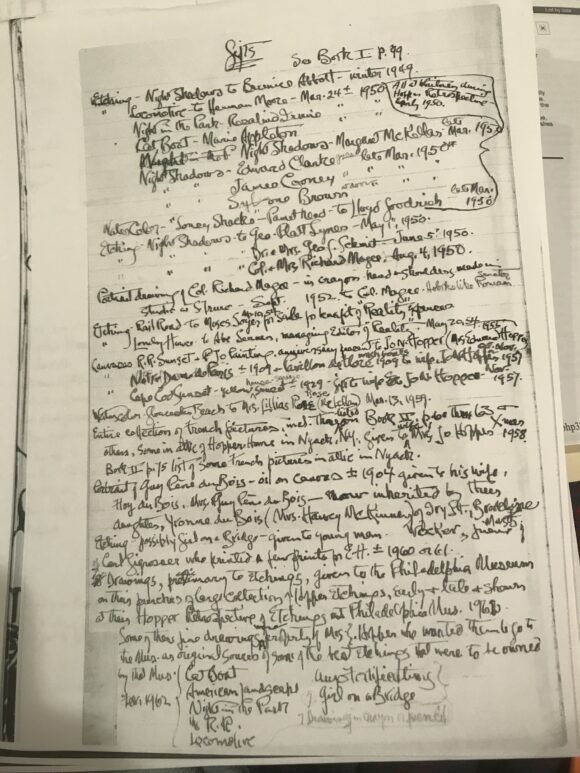

A list of gifts from Edward Hopper’s record books in Jo Hopper’s handwriting. Arthayer R. Sanborn is not listed anywhere in any of the record books.

The above removal of art in December 1967 is related to the removal of the piece of antique furniture that the New York Times investigative reporters Kevin Flynn and Robin Pogrebin uncovered in their 2012 New York Times investigation. They interviewed a neighbor of the Hopper house, who testified that Sanborn came to retrieve the piece of antique furniture that he had asked them to store for him as soon as Sanborn heard that Jo had died. Sanborn thus cleverly kept the antique furniture that he wanted away from the rest of the residual legatees, so that he alone could take it for himself. That is theft! Sanborn was but one of six residual legatees, none of whom were left any art works, all of which were clearly bequeathed to the Whitney Museum, excepting the contents of the Hoppers’ Truro house, which were left to Mary Schiffenhaus. Like his stealth in taking furniture, this is also how Sanborn took art works—secretly, while cooking up his various stories to explain his possession of so many art works. Sanborn even eventually inventing for himself the persona of the expert on Hopper’s ancestry and art, especially in Nyack (which is where his selectivity of what he stole came into play; he also stole selectively to support his own interests in local color and this invented persona. He played upon local pride in Edward Hopper as their native son.) Listen again above to the audio recording of him telling about it in his public lecture of July 22, 1982.

Among the other paintings and drawings that Sanborn took are simply ones that he thought would not be missed and that he could get away with. He sold many of them anonymously and indeed in the beginning, I was unaware that they had come from Sanborn. (I now suspect that he sold etchings and their preparatory sketches taken either from the attic or during his visits to the New York studio, while Jo survived there vulnerable and alone after Edward’s death.) I only knew about the Kennedy Galleries consignment in the broadest terms, not about all of the objects to be sure, nor even the provenance of all of the work in the 1977 Hopper exhibition catalogue for which I wrote an essay for Kennedy Galleries at the request of Tom Armstrong, the director of the Whitney Museum. Armstrong then bragged about this catalogue essay to the museums’ trustees (big red flag is his memo to the trustees, with a copy to me, that I still have!)

He sold many of them anonymously and indeed in the beginning, I was unaware that they had come from Sanborn. (I now suspect that he sold etchings and their preparatory sketches taken either from the attic or during his visits to the New York studio, while Jo survived there vulnerable and alone after Edward’s death.) I only knew about the Kennedy Galleries consignment in the broadest terms, not about all of the objects to be sure, nor even the provenance of all of the work in the 1977 Hopper exhibition catalogue for which I wrote an essay for Kennedy Galleries at the request of Tom Armstrong, the director of the Whitney Museum. Armstrong then bragged about this catalogue essay to the museums’ trustees (big red flag is his memo to the trustees, with a copy to me, that I still have!)

- Exhibition catalogue from 1977, produced with no provenance, mixing works stolen by Sanborn with others on the resale market

- Listing of works in the Kennedy Galleries exhibition without any history of ownership.

Why would a Whitney Museum director want his new curator to write for a commercial gallery? This essay was for a commercial gallery catalogue with no provenance listed for anything. The catalogue and show mingled works by Edward Hopper with “clear title” that were bought on the open marketplace with others from Sanborn’s stolen booty, consigned to Kennedy by Sanborn. Something was amiss here! Did Larry Fleischman, the late owner of Kennedy Galleries, pay off the Whitney or someone on staff, i.e. Lloyd Goodrich or Tom Armstrong (the former and current directors respectively), both of whom encouraged me to accept Fleischman’s payment for my essay of $250.? That $250 seemed like a lot of money at the time when my annual salary at the museum was $16,000. So what did Fleischman pay Goodrich for his short essay in the same catalogue? I doubt that these sums are documented in the gallery records now at the Archives of American Art! And did he also pay Armstrong?

- Larry Fleischman: paying the Whitney to help launder Edward Hopper’s art stolen by Arthayer R. Sanborn?

- Lloyd Goodrich: Curator of 1964 Hopper retrospective; dealt with Larry Fleischman and wrote another essay to help launder art stolen by Sanborn.

- Tom Armstrong: also on the take?

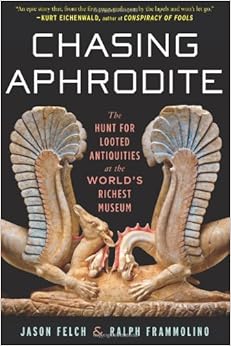

I don’t know. But this exhibition and its catalogue effectively laundered the art that Sanborn stole. It announced to the market and to other museums that the Whitney, the recipient named in Hopper’s will, intended to do nothing to retrieve its rightful inheritance. Fleischman is now famous for having bought and sold (and given to the Getty Museum, in a typical tax evasion deal) a huge collection of ancient art objects some of which had been stolen by tomb robbers in Italy and have since have had to be returned to the government of Italy. See this story of Fleischman’s laundering stolen art in the book, Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities in the World’s Museums by the fearless jounalists, Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino.

See also Michael Kimmelman’s December 8, 2005, New York Times article, “Regarding Antiquities, Some Changes, Please.” Excerpted here:

And if the Getty’s former antiquities curator, Marion True, and her bosses at the museum did not suspect that some of the objects they acquired from a trustee, Barbara Fleischman, and her late husband, Lawrence, were hot, then they were just about the only people in the art world who didn’t.

Most of people who were involved in this scheme in which Arthayer R. Sanborn stole art works from the estates of Edward Hopper and Jo Hopper are now dead. Yet these stolen art works were all bequeathed to the Whitney Museum by Jo Hopper and should have gone into the museum’s tax-exempt collection. Thus, I am still trying to expose the truth. I am motivated by learning in July 2017 that Sanborn had kept more than 4,000 documents from the Hoppers’ papers from me while I was struggling (under the pressure of a timetable set by the museum) to research and write the vast catalogue raisonné of Edward Hopper commissioned by the Whitney. And then there is the fact that Sanborn manipulated me, an innocent young scholar, to authenticate his stolen art at the same time. That seems downright cruel.

- Gail Levin ca 1979, as a young curator at the Whitney Museum, working on the Edward Hopper Catalogue Raisonne

- Edward Hopper: Catalogue Raisonne by Gail Levin, published in 1995 by W.W. Norton & Co. for the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In today’s market a single Edward Hopper oil painting like City Roofs, 1932 from Sanborn’s haul is worth upwards of 40 Million Dollars. Now that I am aging too, the Whitney is counting on the fact that I won’t be around for that much longer and they can bury this sordid tale for all time. I just want the truth, the facts of what really transpired, see the light of day. I want the public to know what happened to this famous artist’s estate. I don’t want to see Sanborn celebrated as a hero when he was in fact a thief. I stood in his way and he needed to fool me. When that proved too difficult and I tried to blow the whistle, I had to be gotten rid of and so the museum fired me in a harsh and humiliating manner: 30 minutes to vacate the premises. I am not sure of the details of its deal with Sanborn, but I am now confident that this is what happened.

One big clue is the purchase by the Whitney from an anonymous seller (of course) of the extra Hopper record book, which was then loaned to me by the museum to complete the catalogue raisonné (After June 1984, I worked for free at home without a fee, since as a professor, I needed to finish this publication on which I had invested so much time and energy to advance in my academic rank). My scholarship for the drawing and prints volumes remained unfinished and, like the archives I constructed, has been used by countless others without credit to me. This extra record book, which the Whitney claimed to have purchased, had to have come from Sanborn. It was not from the Hoppers’ Cape Cod House (Mary Schiffenhaus’s inheritance) and there is no other possible source. The record books were all to have gone to Lloyd Goodrich according to Jo Hopper’s will, but Sanborn got some of them instead. I know of yet another Hopper record book, still in a private collection, which Larry Fleischman obtained from Sanborn. Fleischman, owner of Kennedy Galleries, then gave this record book to one of his big clients. This record book, too, should be with the others and the more than 4,000 other documents given to the Whitney in 2017 by the Sanborn heirs, after these papers had been suppressed by the preacher and his family for 50 years after Edward Hopper’s death. Is this the way that the art market works in America? Thieves hold their ill-gotten booty for decades, until their heirs can give it away for a tax deduction? Museums collaborate with thieves. Who pays for such a system? We the tax-paying public pay! The rich folk and the thieves make out like bandits! Where is Congress on legislation to stop this?

We still need to understand why the Whitney Museum took this course to cover up its own losses instead of fighting for art, which was clearly bequeathed to the museum and why the museum’s administration and its trustees still want to obfuscate the truth. I suggest that some honest journalists look into all of the above and not accept the first version of what transpired in these matters. There is a lot of cover-up going on!

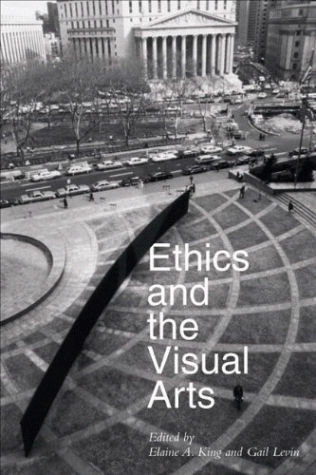

During my research trip to Boston in June 2019, I happened to notice on the website of the MFA, Boston, a statement about the MFA’s 2007 Edward Hopper show and catalogue, which I had previously ignored. But now it seems to tie a few things together. The MFA, Boston, held an Edward Hopper retrospective in 2007, curated by Carol Troyen, who had not published previously on Hopper or at least nothing that I had come across. She was not on the staff when my 1979 Whitney show, “Edward Hopper: Prints and Illustrations,” traveled to the MFA Boston, where it had great success. I had not previously known Troyen, so I asked to meet with her, and when we met, I asked if I could contribute an essay to the forthcoming catalogue. This would not have been an unusual arrangement, but for my history with the Whitney, which controlled a lot of the loans. Troyen replied that I could have nothing to do with her show, which even turned out to include my giving lectures at any of its venues. I understood the unstated: that the Whitney Museum had made sure that I could have nothing to do with a show to which it was lending. This was just a year after my first essay on Arthayer R. Sanborn and this theft came out in my 2006 co-edited anthology, Ethics and the Visual Arts. At the time Sanborn was still alive.

This anthology tells the story of Sanborn’s theft in my essay, “Artists’ Estates: When Trust is Betrayed;” the collection was edited by Elaine A. King and Gail Levin for Allworth Press, in New York. in 2006.

The 2007 show of Hopper at the Boston MFA traveled to the National Gallery in Washington and to the Art Institute of Chicago. Both museums refused to have lectures by me, even the Art Institute, which had hosted the big Hopper show that I organized in 1980-81. I had lectured there then and the well-attended lecture, like the show, was a big success. I had since published an essay on Hopper in the Art Institute of Chicago’s journal. But the director had since changed and the Whitney had upped its attack on me. I even had a patron, Phil Krone, in Chicago, who offered to sponsor a lecture by me at the Art Institute of Chicago, but they declined his offer to finance a lecture by me. (Krone hosted it instead at his private club and then we all visited the show at the museum.) The National Gallery of Art turned down my request to lecture on Hopper and also left me out of their film on Hopper, using outside “talking heads,” who knew much less about Hopper and drew upon my scholarship without acknowledgment. However, the Corcoran Gallery invited me to lecture on Hopper in the summer just before the Hopper show opened at the National Gallery of Art that fall. I received a standing ovation.

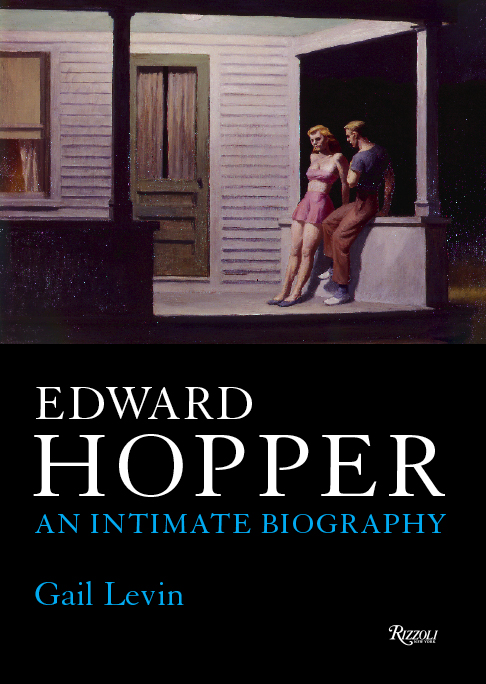

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston website about the 2007 catalogue includes the following notice: “Catalogue by Carol Troyen and Judith A. Barter, with additional essays by Janet L. Comey, Elliot Bostwick Davis, and Ellen E. Roberts. The editors also acknowledge the research of Elizabeth Thompson Colleary on the relationship between Hopper and his wife.” Ironically, the last sentence above about “the relationship between Hopper and his wife” was the well-known theme of my 1995 book, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, 1995; University of California Press, 1998; second expanded edition, Rizzoli Books, 2007).

Elizabeth Thompson Colleary is the person whose interview with Sanborn is at the Whitney, kept under wraps, unavailable to anyone to consult, even in its transcript listed on WorldCat.

Elizabeth Thompson Colleary is the person whose interview with Sanborn is at the Whitney, kept under wraps, unavailable to anyone to consult, even in its transcript listed on WorldCat.

One can only imagine that this, Sanborn’s last known recorded interview, contains a death-bed confession. Colleary has since published a group of insignificant letters sent to Hopper by a female acquaintance from the years before he married Jo. Colleary got access to these letters from Arthayer R. Sanborn, who stole them out of the Nyack attic. We can be sure that Jo Hopper would never have given him these letters! Colleary published her slim volume with Yale University Press, supported by the Whitney Museum, labeled in the book: “Published in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art.”

Yet this book had no plausible connection to any Whitney show. Colleary, I now know, routinely shadowed me, before I knew what she looked like. She would sit in the first row of seats when I lectured, recording me. When she was identified to me by the museum director in Provincetown on September 9, 2017, I approached and spoke at length with her. I learned from her that some “anonymous donor” had given the Whitney a donation to support her work on the Hoppers! I would guess that the donor was Arthayer R. Sanborn, paying to have his reputation cleansed.

At the time of the Tate Gallery Hopper show in 2004, evidently unable to publish in a prominent place on her own, responded in a hostile manner to my essay, “Mr. and Mrs. Hopper,” on Edward and Jo Hopper in the London Review of Books.

Colleary falsely claimed in the London Review of Books that the 96 framed works by Jo Hopper that were given by the Whitney to New York City hospitals were not really missing and that no other canvases had been discarded. (She later published this untruth in an article in Women’s Art Journal). I believe that Colleary was trying to curry favor with the Whitney and that she may even have been put up to doing this by the museum. Colleary also tried to claim that these works by Jo Hopper were merely loans from the Whitney to New York City-area hospitals, but since they were abandoned for decades, it’s not conceivable that they were loans: some of these 96 framed works were watercolors and no museum lends watercolors for more than a month or two, due to fading of the colors.

Speaking with Colleary that day after my lecture in Provincetown, I learned from her that she knew how the Whitney got back Obituary, the one painting by Jo Hopper that I showed in my lecture in color, after downloading it from the Whitney website. Despite the fact that the Whitney had given it away to a hospital, the museum’s website showed a fake accession number from 1970, which I mentioned in my lecture. Her story was that an artist found it in a flea market and brought it to barter with the Whitney, hoping to obtain a show.

I am going over all of the above because it links Sanborn to Colleary to Troyen to the Whitney. When the Whitney sent out the July 29, 2017 press release for the gift of the Hopper papers from Sanborn’s heirs, whom did it quote but Carol Troyen referring to the “Sanborns’ generous donation.”

Some enterprising journalist should interview all of the above and not accept their first version of what transpired in these matters. There is a lot of cover-up going on!